Reformation Cardinal

Reginald Pole in sixteenth-century

Italy and England

Welcome to our interactive digital exhibition.

Click on each of the image links below to explore the exhibited items in more detail.

‘Perhaps the most virtuous and learned and grave young man in all of Italy’

Pietro Bembo, humanist poet and later cardinal, in 1526

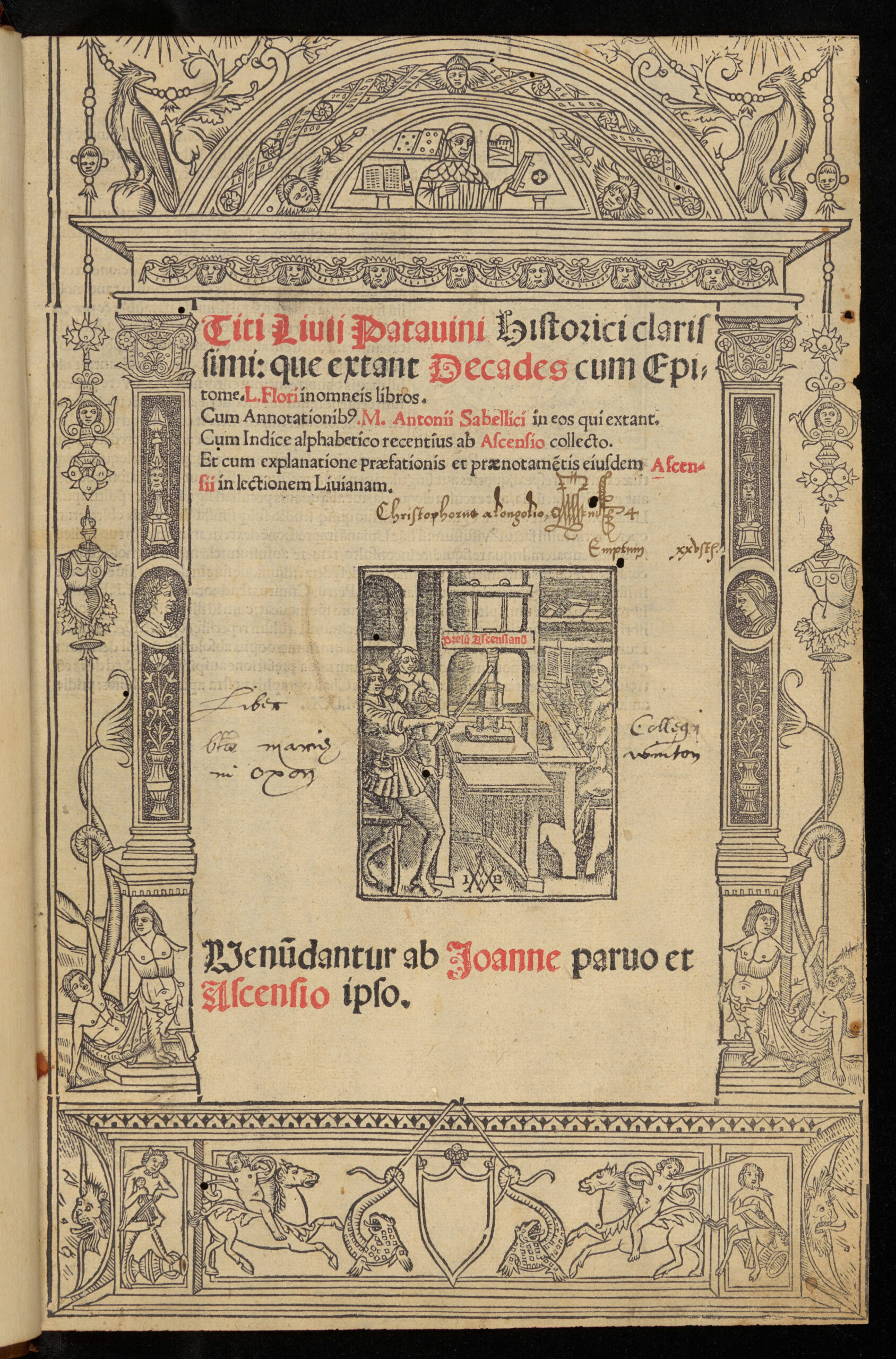

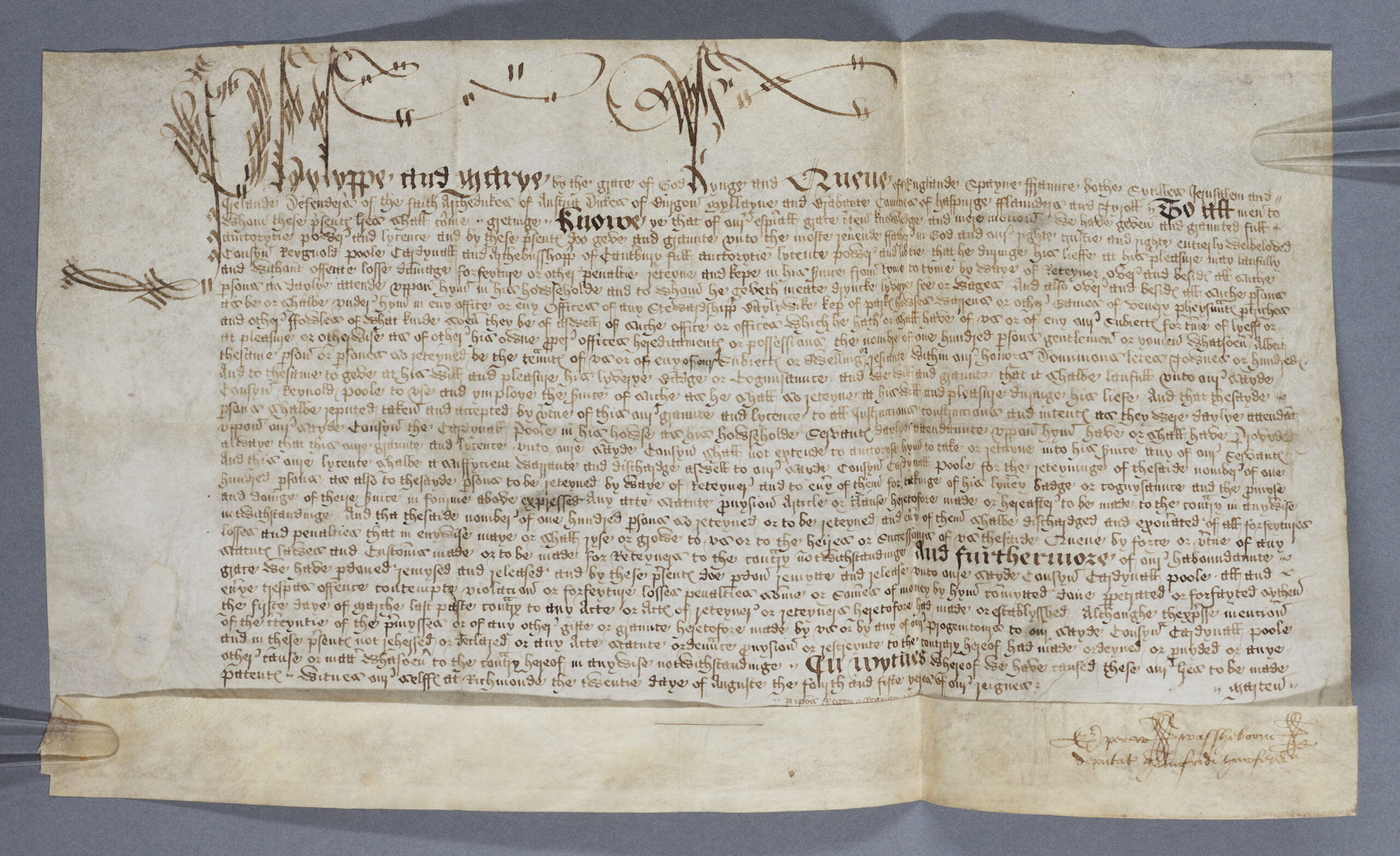

Reginald Pole was born in 1500 to a grand but ruined inheritance, his family having been stripped of lands and wealth by Henry VII. Taking descent from the Plantagenet royal line, Pole’s claim to the throne of England was in fact rather better than that of the reigning Tudors. His second cousin, Henry VIII, kept him close, fostering Reginald’s career in the Church. After an education at the Charterhouse at Sheen, close to Richmond Palace, and at Magdalen College in Oxford, Henry sent Pole to Padua in Italy. There, he was first drawn into the circles of Italian humanistic scholarship that would so closely define his formation. He was lodged magnificently in the Palazzo Roccabonella—as befitted his rank if not his means—and he opened its doors to an international cast of scholars. It became conventional to praise Pole for being as virtuous as he was noble, as noble as learned, and no one forgot how close he stood to the throne.

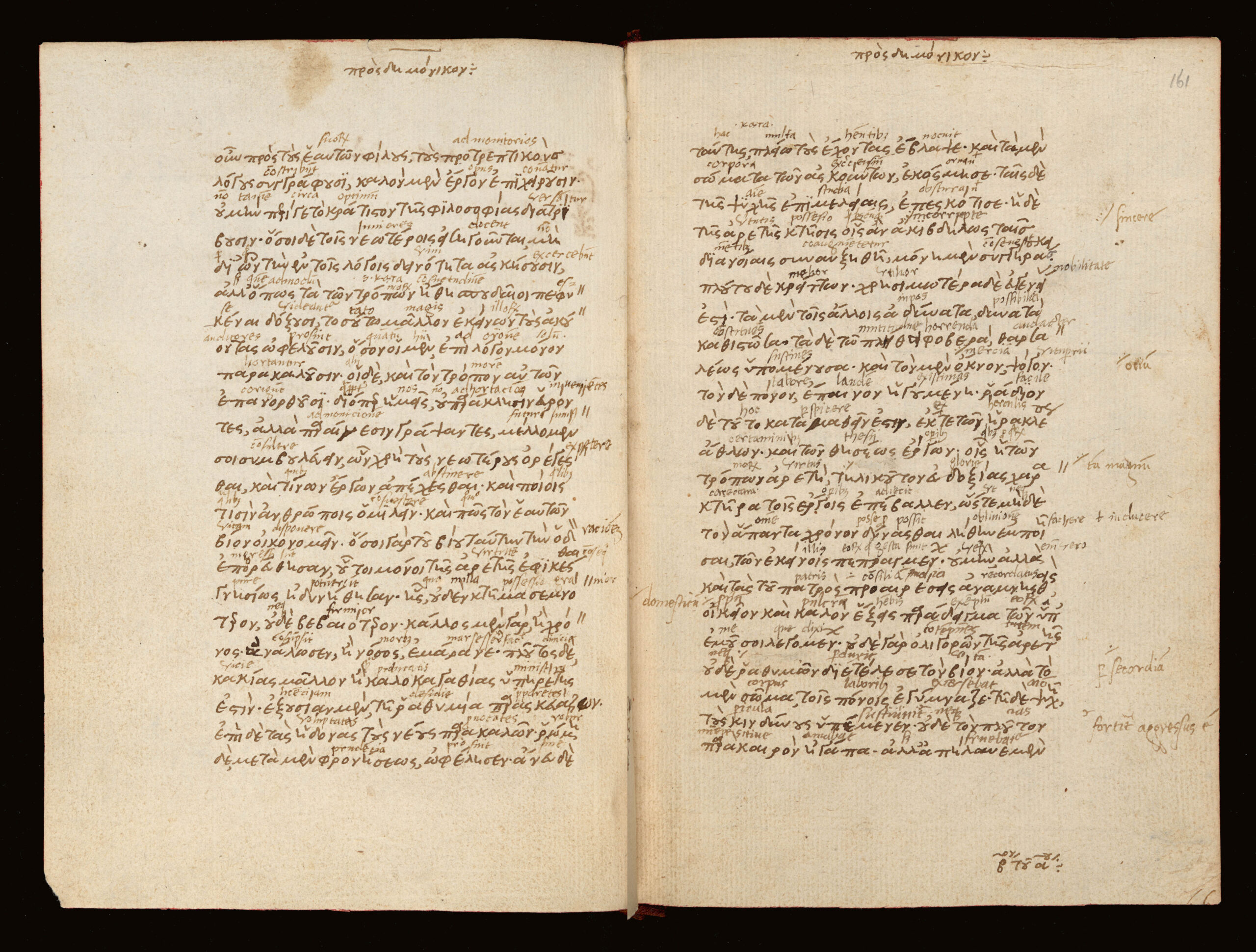

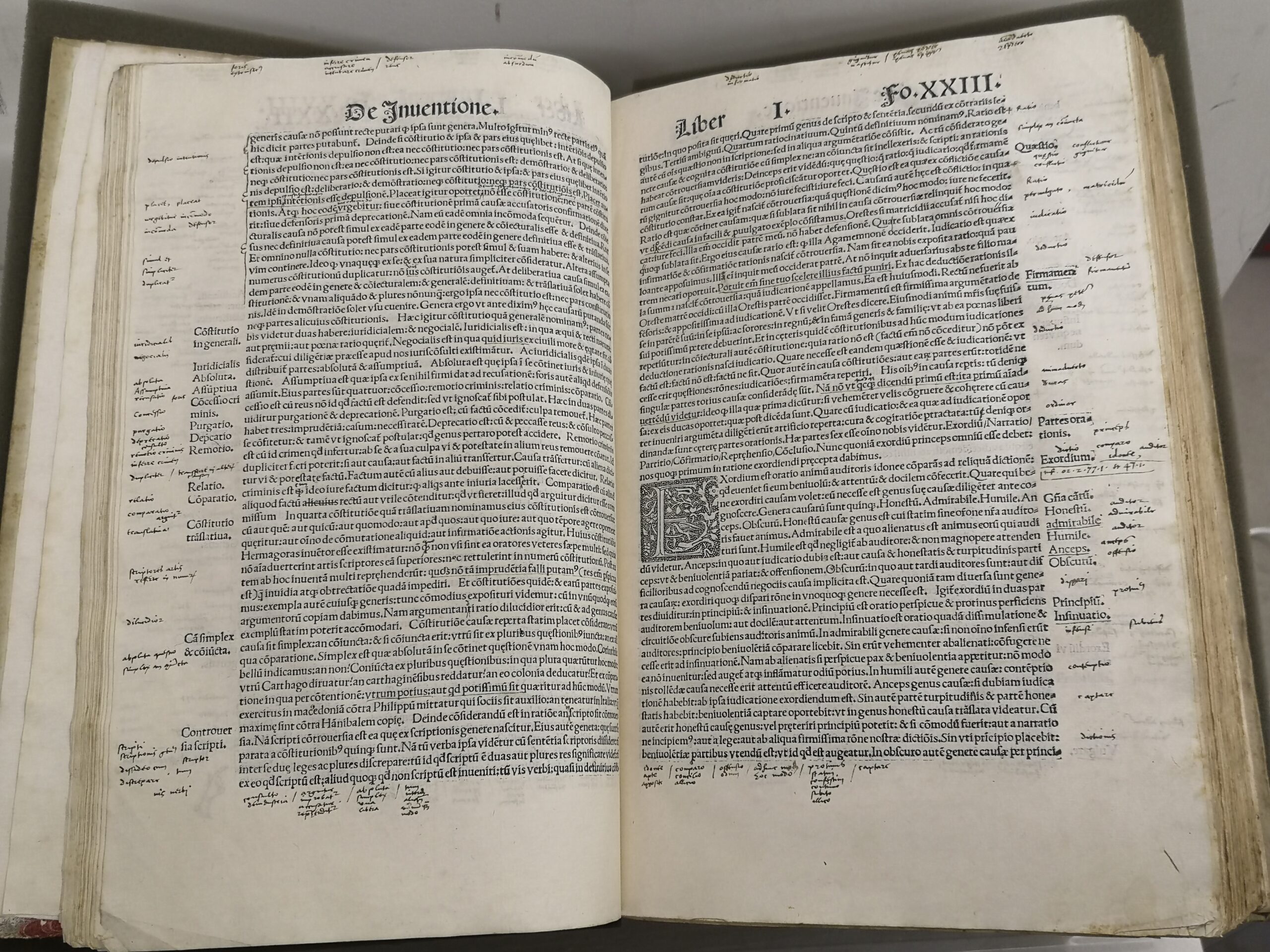

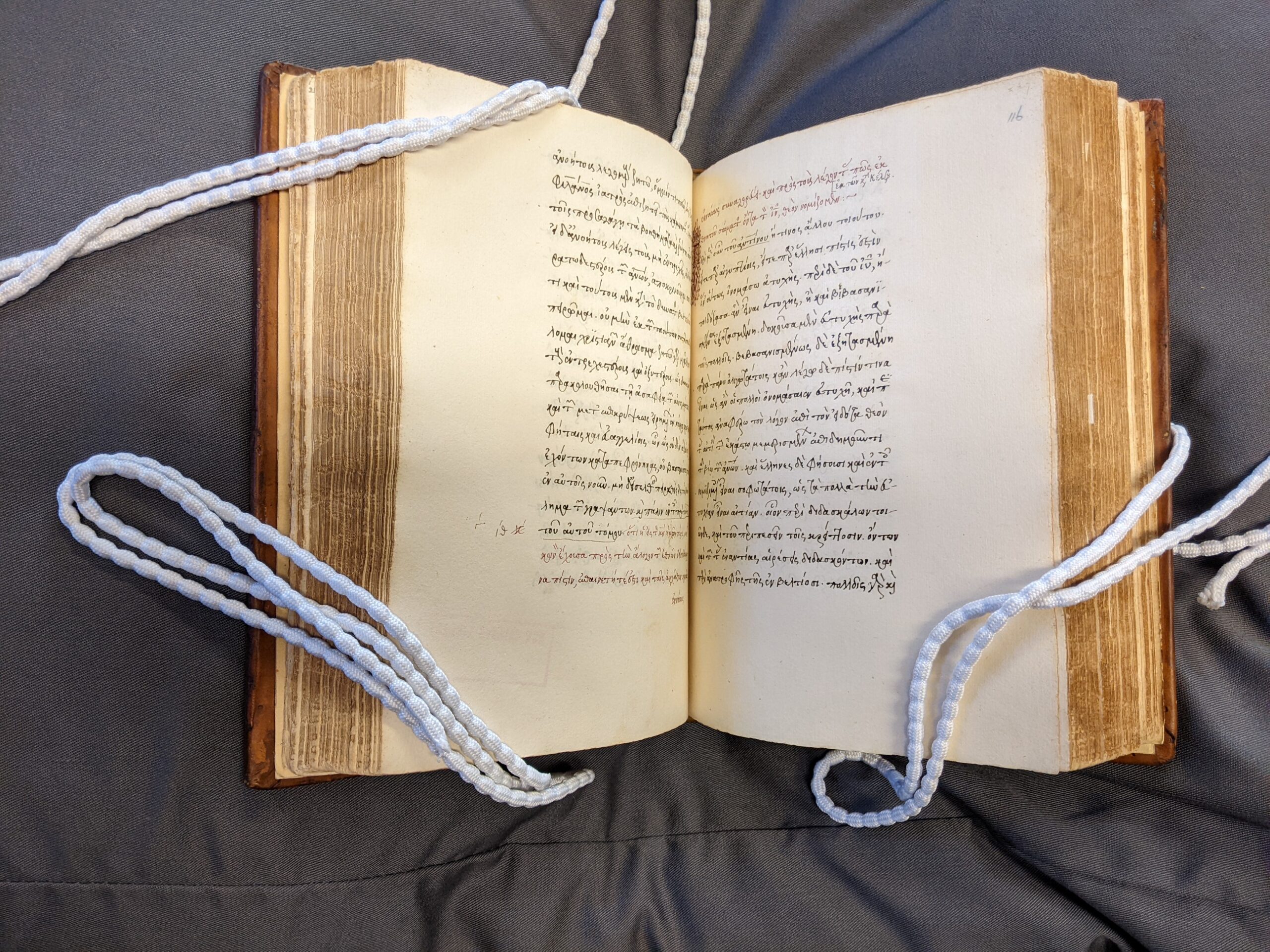

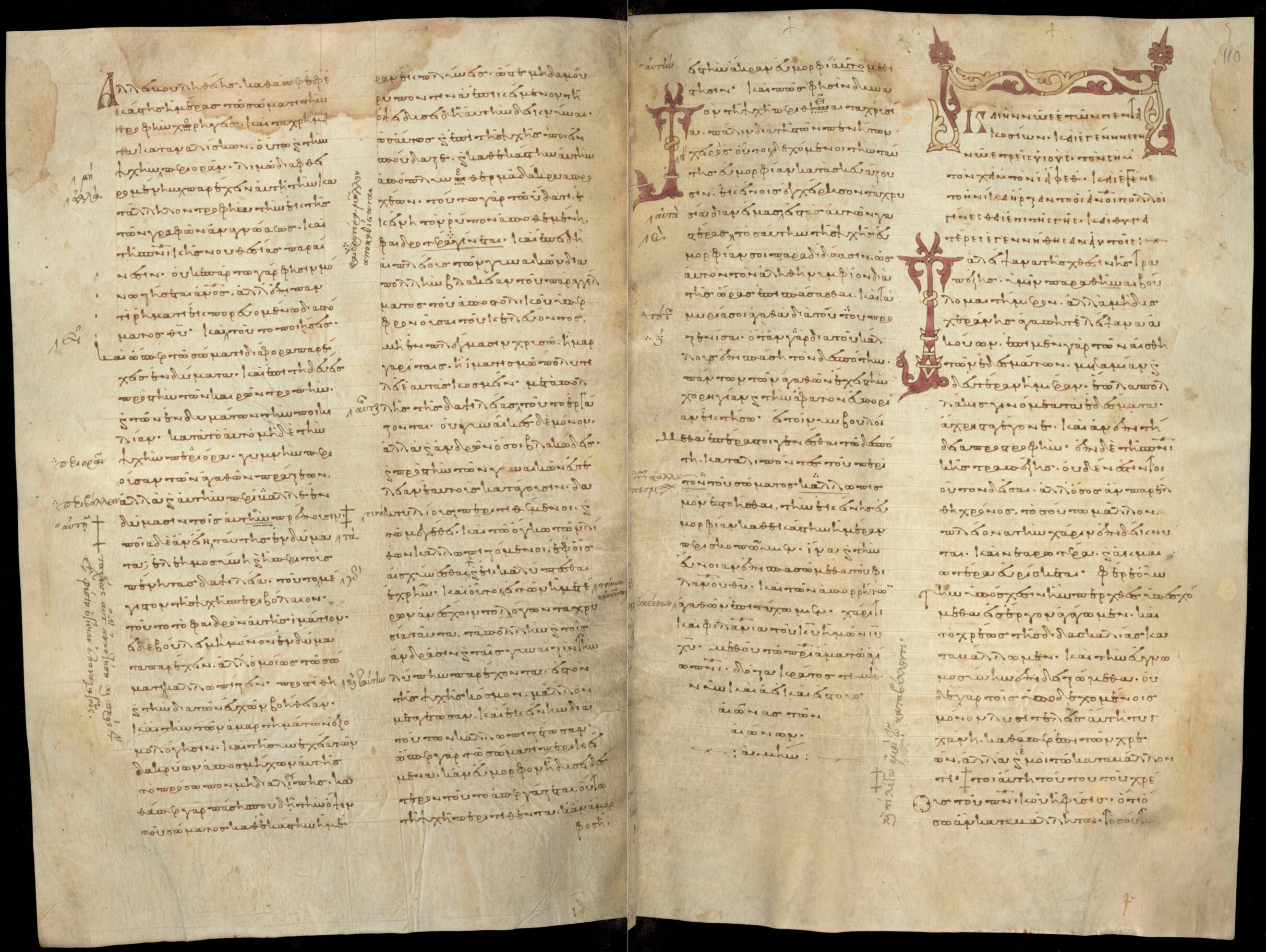

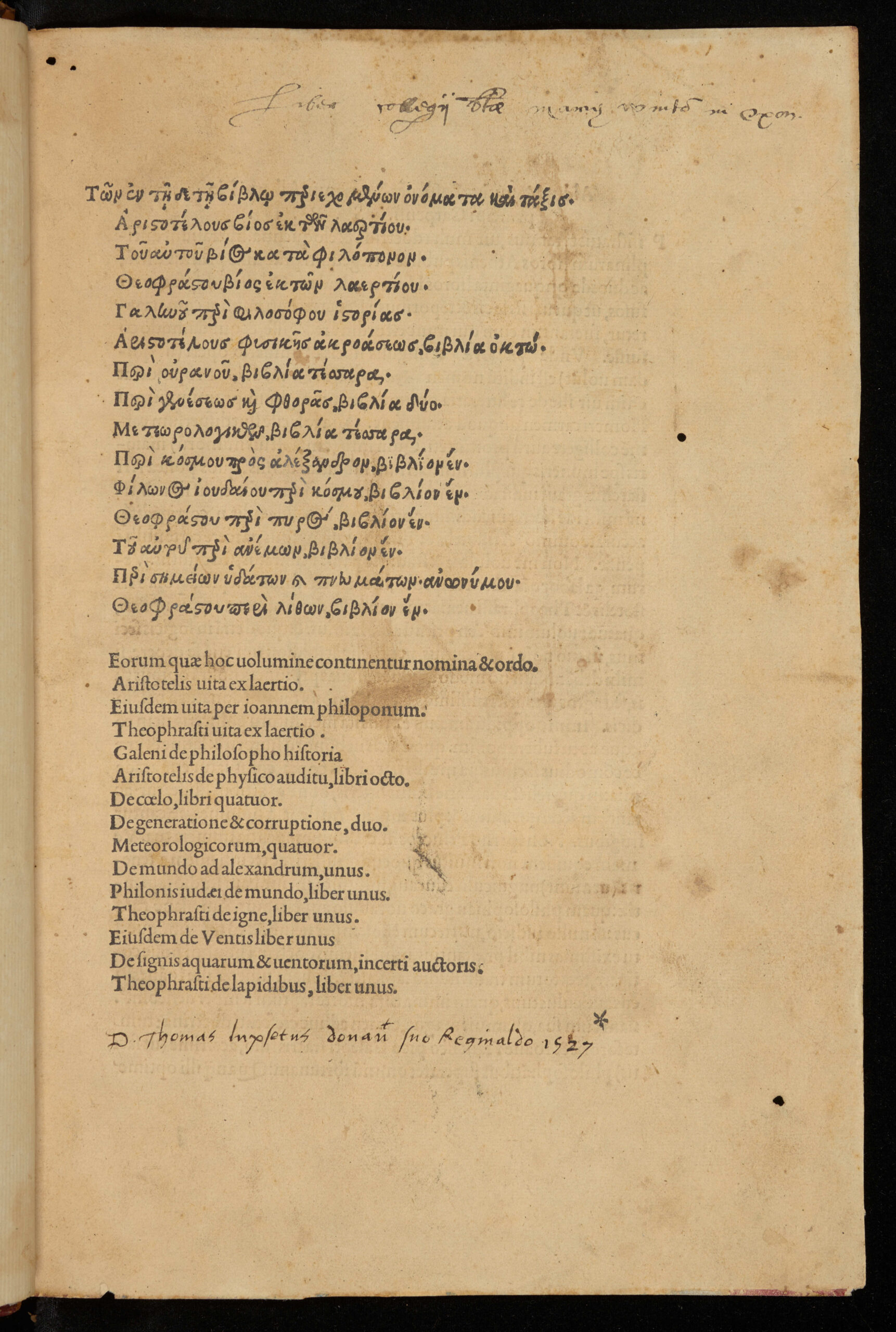

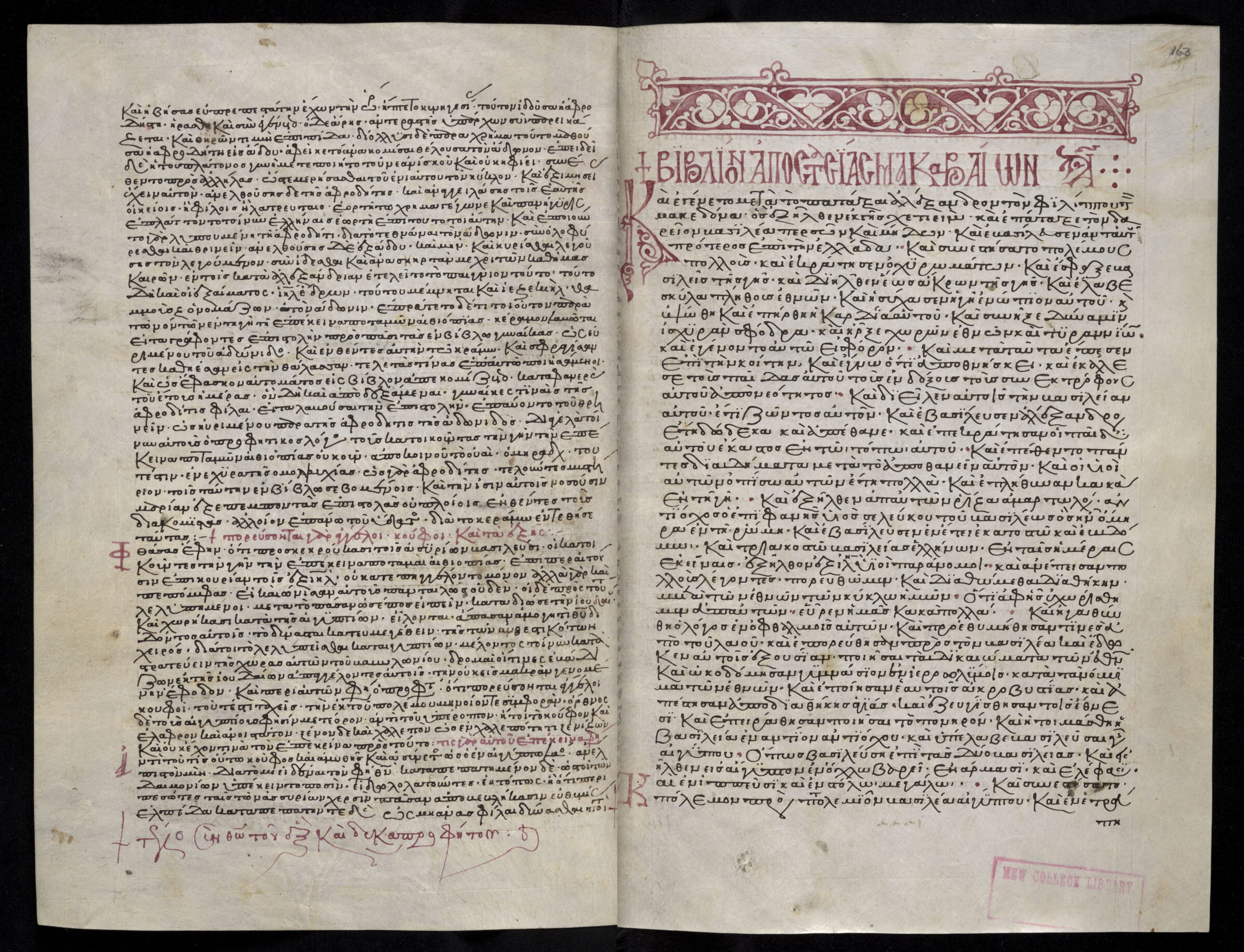

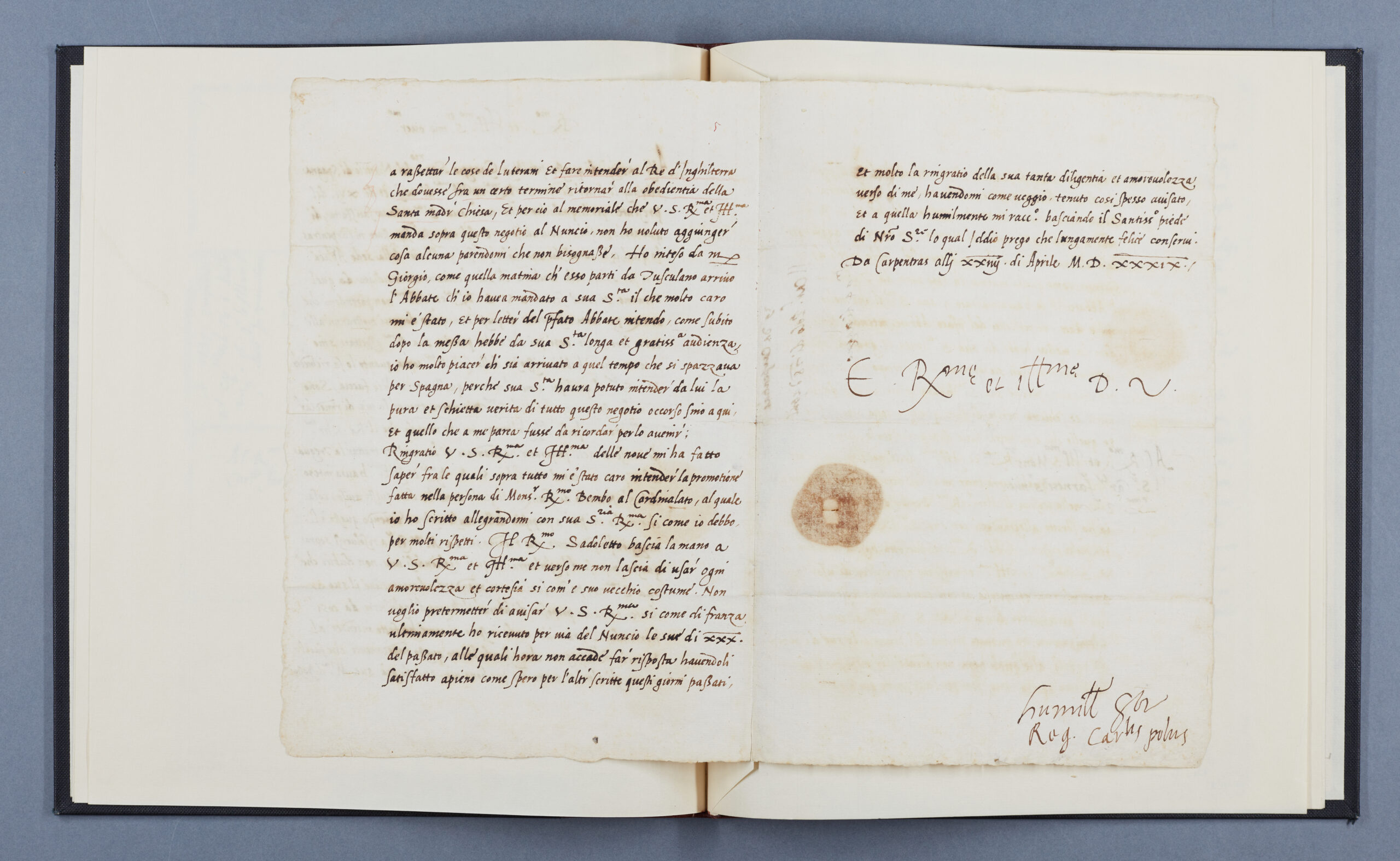

Pole was taught Aristotelian logic and natural science by Niccolò Leonico Tomeo, a leader of the Hellenic renaissance in Padua. He formed strong friendships with, among others, the Venetian poet and nobleman Pietro Bembo, with his Oxford tutor Thomas Linacre, founding father of the Royal College of Surgeons, with his fellow student in Padua Thomas Lupset, and with Christophe de Longueil (known as ‘Longolius’), Europe’s leading Ciceronian, who joined Pole’s household.

‘For one Pole’s sake the King would destroy all Poles’

Thomas Starkey, Pole’s friend, in 1538

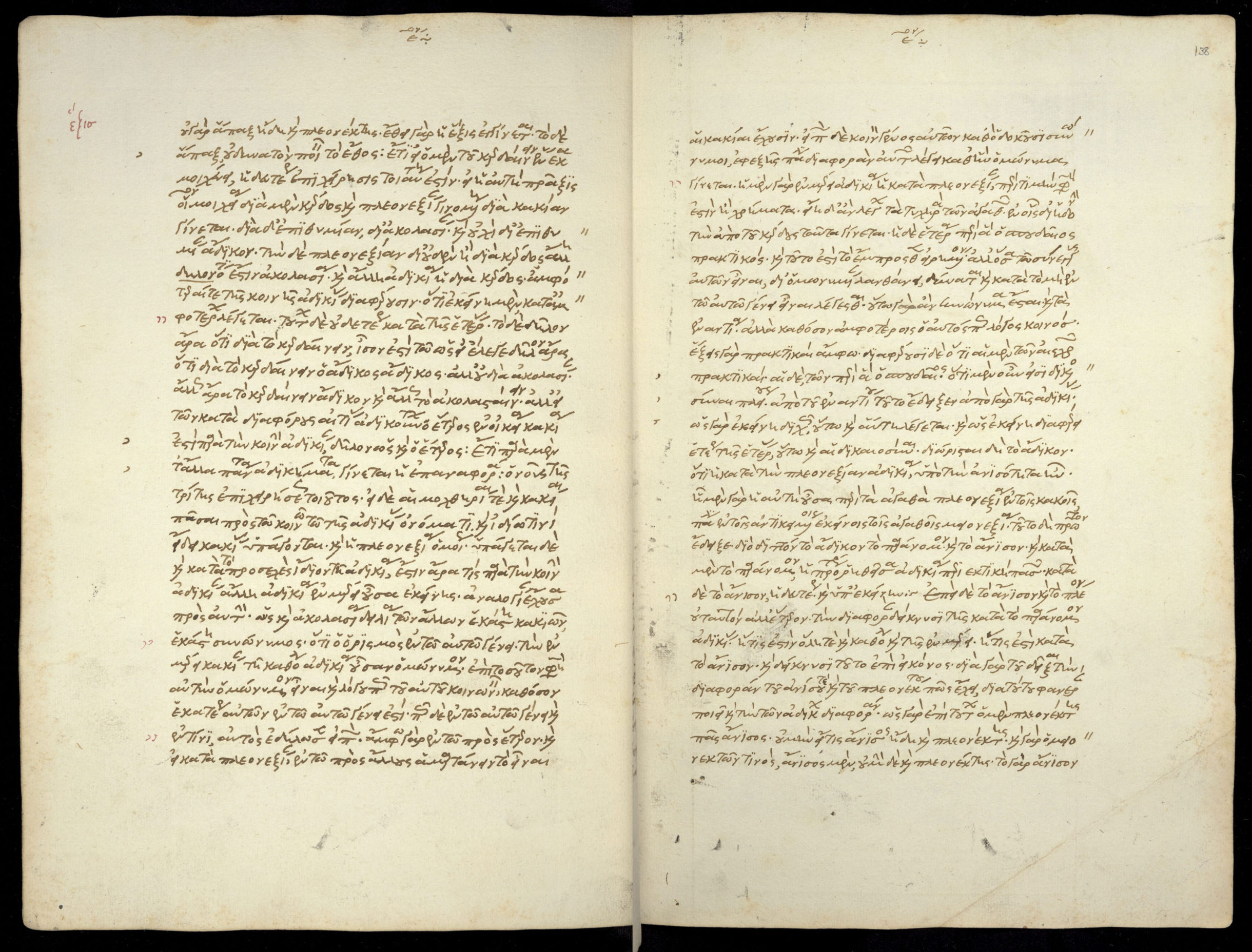

In 1526 Pole returned to England and scholarly seclusion at Sheen, extending his studies from Greek to Hebrew. He refused the king’s offer of bishoprics, and friendly letters and discourses on natural leadership could not coax him into English public life. In fact, he was turning towards opposition. He could no longer support the king in his divorce from Katharine of Aragon, and told him so. Early in 1532 he returned to Italy to resume his studies in Padua and Venice. There, in the words of a contemporary, he underwent ‘a great change, exchanging man for God’.

Events forced Pole to break his public silence. In the summer of 1535 the bishop of Rochester, John Fisher, and the chancellor, Thomas More, were executed for refusing to accede to the royal act of supremacy over the English Church. Pole explained how these executions finally clarified his mind. ‘As soon as I had composed myself, I considered that I had always agreed with these men and should no longer keep my opinion hidden.’ The result was a book, De unitate, an impassioned argument for the unity of the Western Church against the assumption of supremacy by Henry VIII, to whom the work was audaciously addressed.

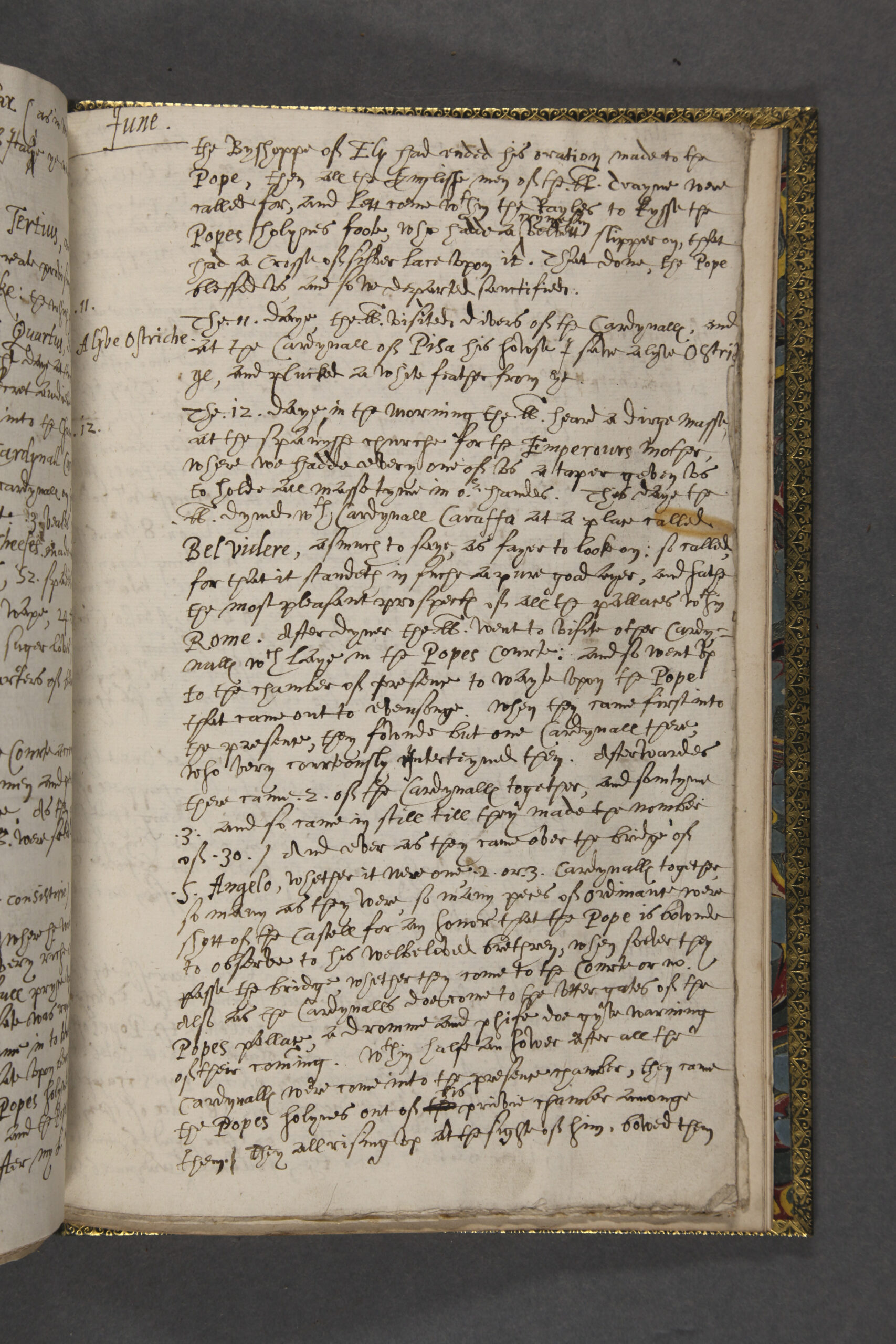

Henry’s fury was immediate. A bounty of 100,000 gold crowns was put on Pole’s head and his family in England was hounded by the regime. In 1538, the discovery of a supposed plot against the Crown, the so-called ‘Exeter Conspiracy’, resulted in the execution of Pole’s brother, Henry Baron Montagu, and cousin, Henry Courtenay, marquess of Exeter. Three years later his mother, Margaret, countess of Salisbury, was also sent to the scaffold.

‘In Rome he was regarded as a Lutheran and in Germany as a papist’

Thomas Starkey, Pole’s friend, in 1538

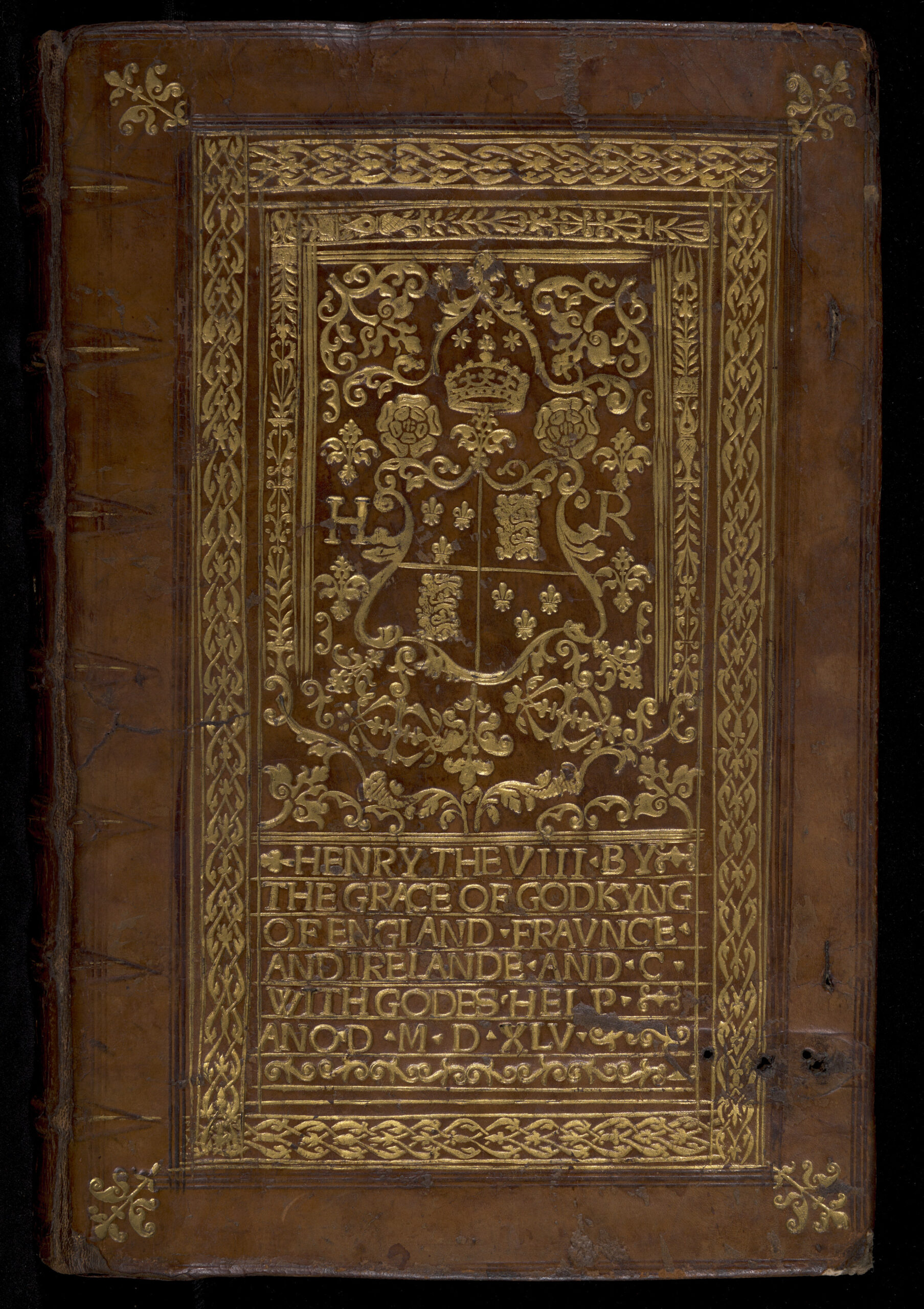

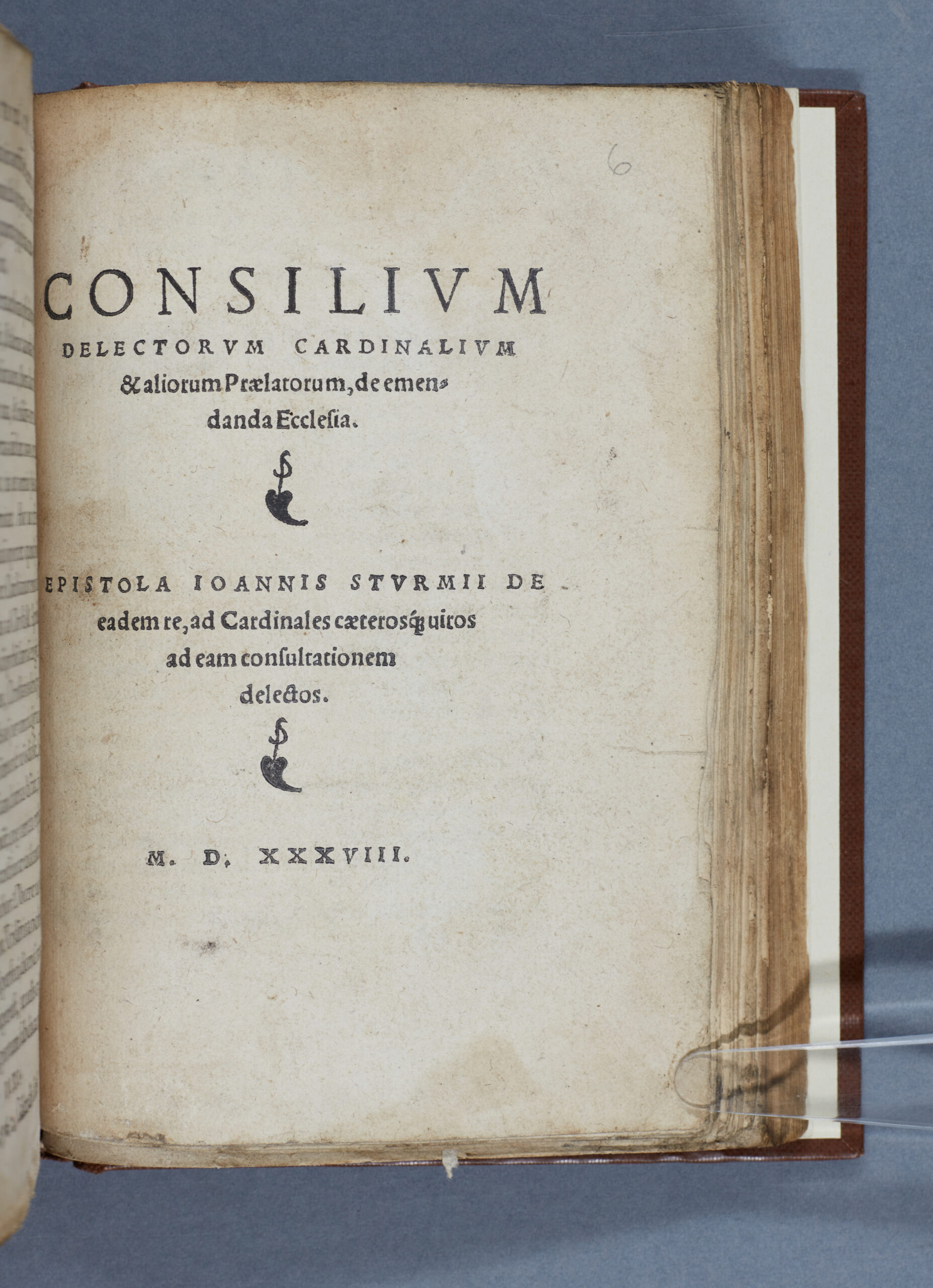

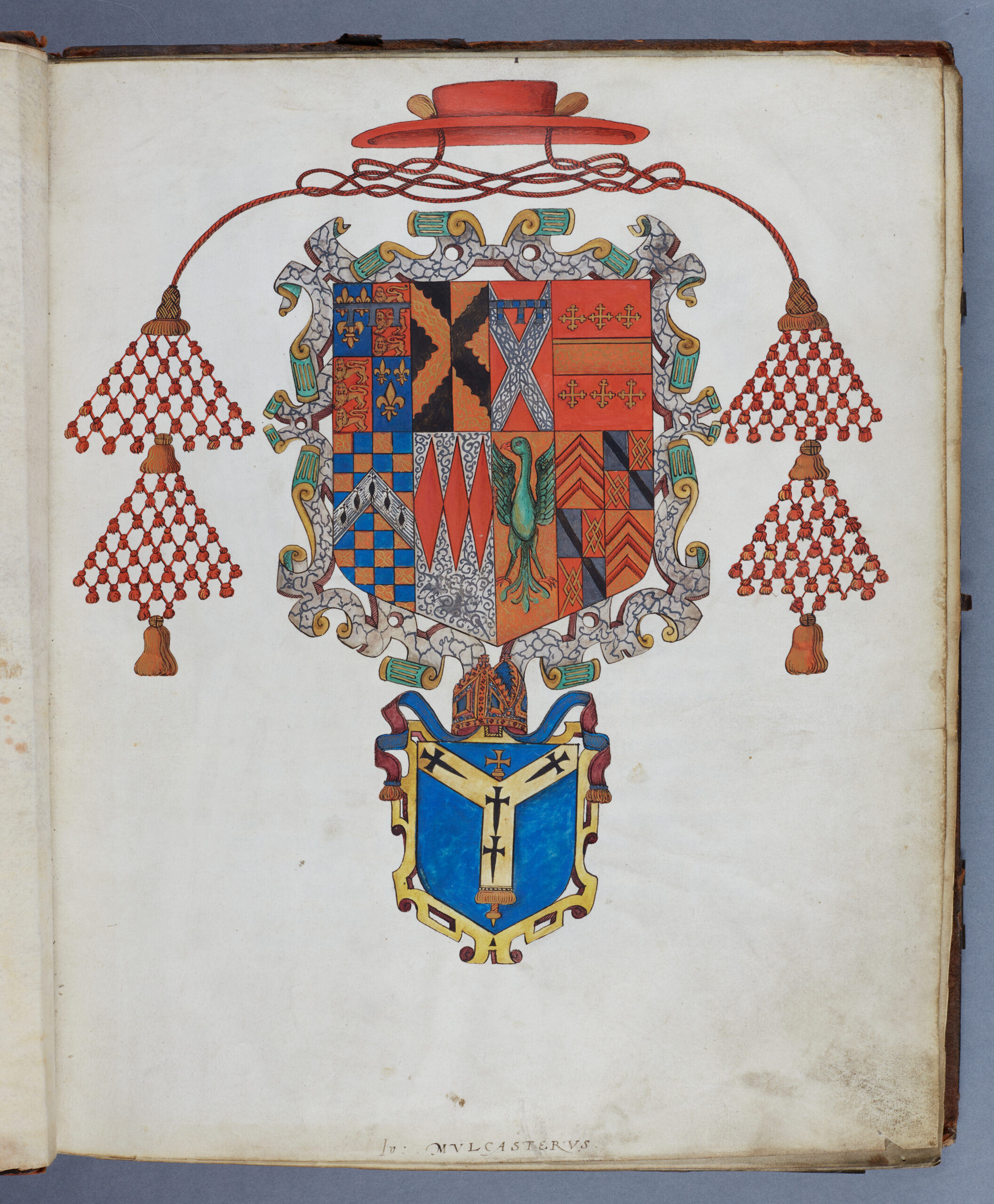

Pole’s impassioned defence in De unitate for the unity of the Catholic Church catapulted him to Rome where he was made a cardinal in 1536. Five years later he was appointed Governor of the Papal States and he moved his household to Viterbo. Pope Paul III appointed him one of the three papal legates to the great Church council at Trent, which first convened in 1545. His was a voice there for moderation, advising the assembly not to argue ‘Luther said that, therefore it is false’.

His position was in fact self-protective. He was exploring new religious ideas through his association with a group of heterodox reformers known in Italy as the spirituali. Their central preoccupation was with the means to salvation for the Christian soul through the divine gift of faith (‘justification by faith alone’). A chief tenet of Lutheranism, the position was held by the Catholic Church to be heretical. In 1542 a colder, orthodox wind began to blow from Rome as plans for the revival of the Inquisition were set in motion.

Of his nature, Pole was reserved and secretive. Only his closest friends knew his mind, and his enemies turned his silences against him. In 1549 his candidacy for the papacy was attacked by the Grand Inquisitor Gian Pietro Carafa, brandishing evidence that Pole was a secret Lutheran. In spite of that, Pole came within one vote of being elected pope. He refused further politicking and withdrew to Viterbo, giving his enemies opportunity to conspire further against him.

‘I come to reconcile, not to condemn. I come not to compel but to call again.’

Pole’s address to the English parliament, 1554

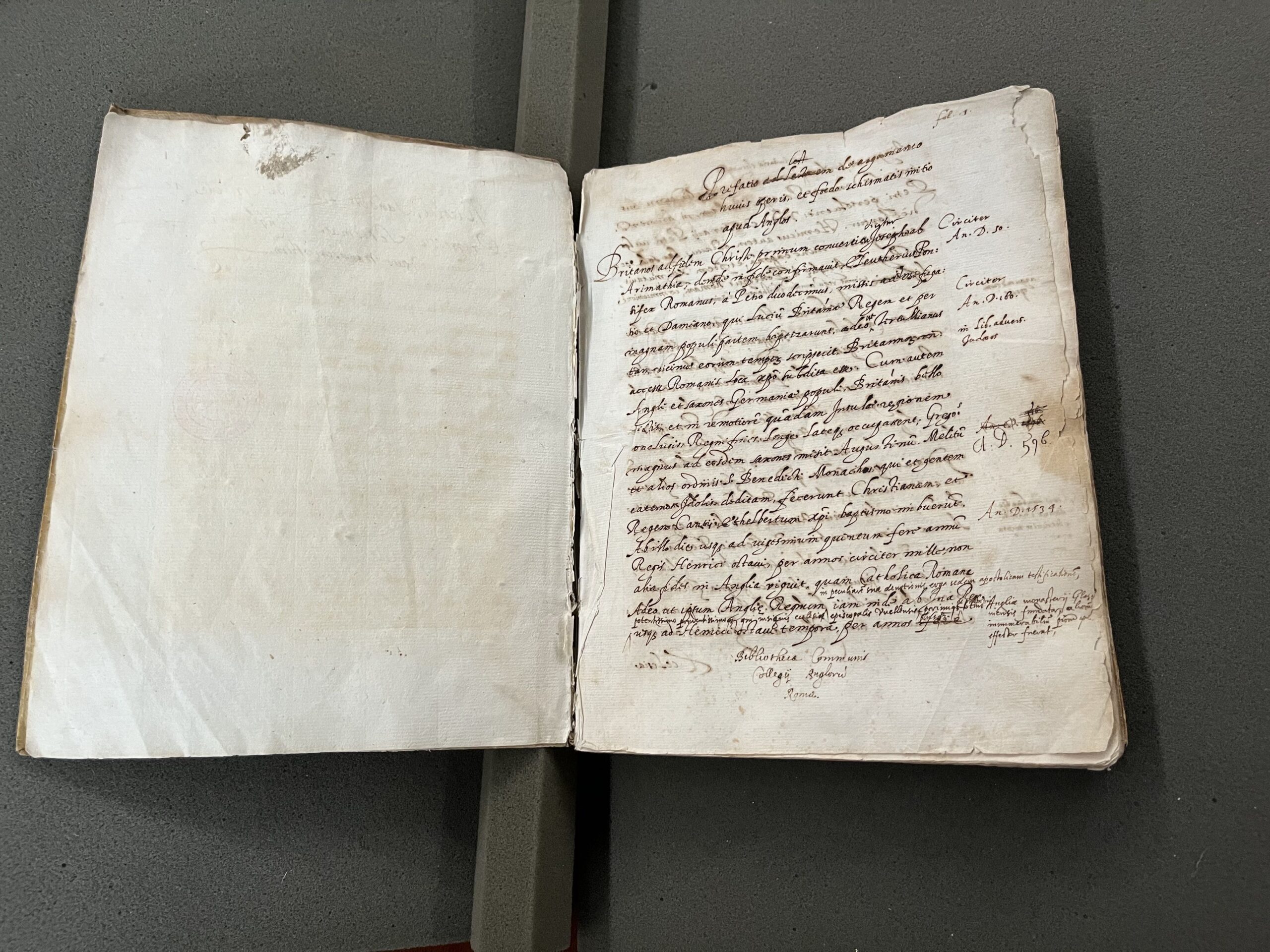

King Edward VI died in 1553 and his half-sister Mary, the Catholic daughter of Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon, became queen. As Mary was strengthening her hold on the throne, Pope Julius III appointed Pole papal legate to England. Days after Pole’s arrival in England the reconciliation of England to Rome was pronounced, in a special evening session of parliament on 30 November 1554. Some sensitivity was shown in the way the reconciliation was staged; Mary requested absolution speaking in English, and Pole, unusually, also pronounced absolution in his native language. Pole and Mary would have just four years in which to reconstitute parish religion, regenerate Catholic learning in the universities, refound monasticism, reform the clergy, and rebuild England’s relationship with the papacy. It is a tribute to Pole’s energy and determination that in that time he made significant advances in all these areas.

He convened a legatine synod in London for the reform of the English Church, and Mary made him Archbishop of Canterbury. He was a very suitable choice. As Mary’s cousin and Henry VIII’s fearless critic, his credentials as an English noble and churchman were impeccable. As a cardinal involved in Church reform, and a man who had almost been made pope, he seemed the obvious person to reunite the English Church with the rest of Catholic Europe. Pole himself would probably have added that his status as the son of a martyr gave him a precious insight into the needs of a Church in crisis.

‘Now is the hour for us to wake from sleep’

Bishop Stephen Gardiner, sermon preached at St Paul’s Cross, 1554

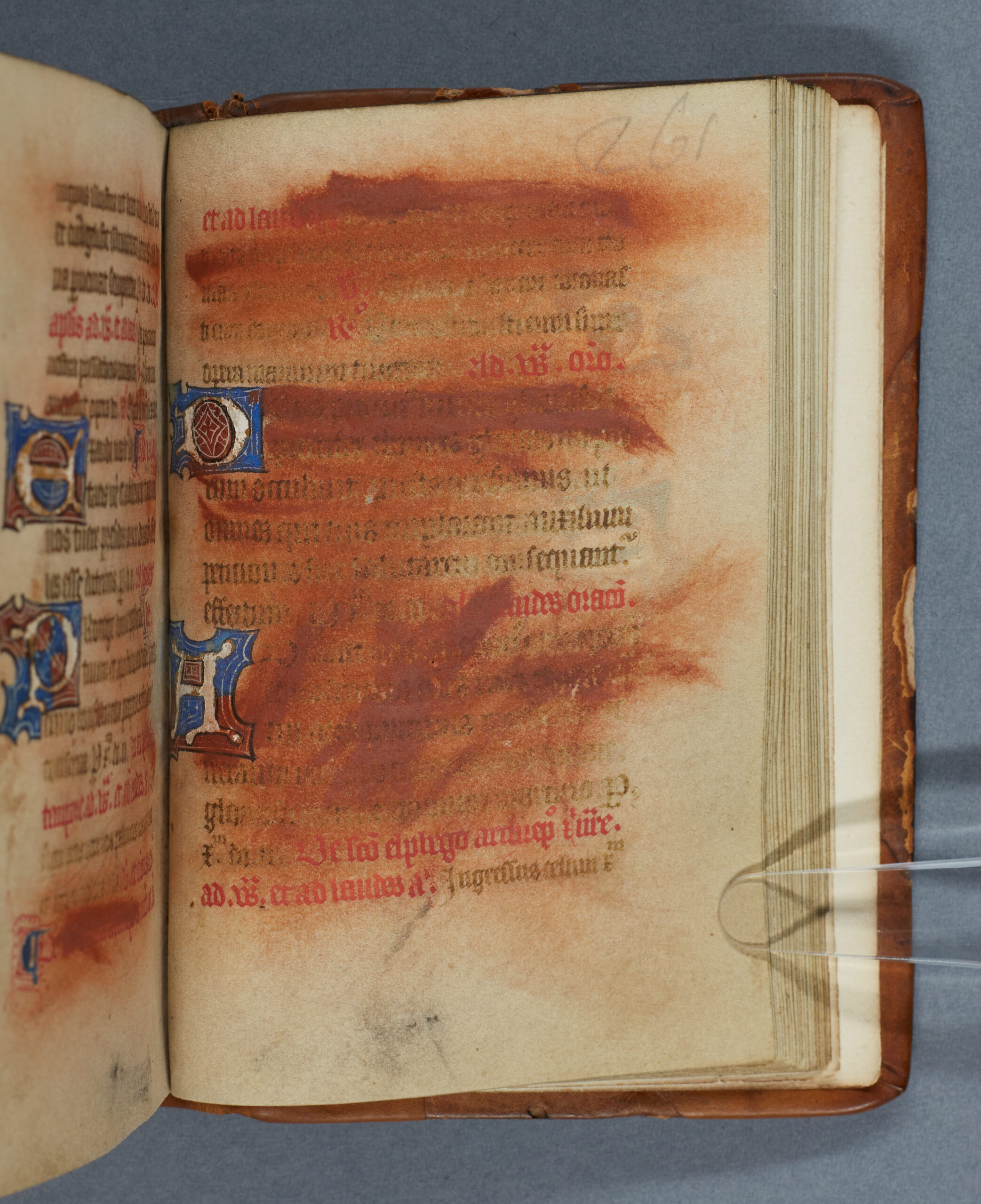

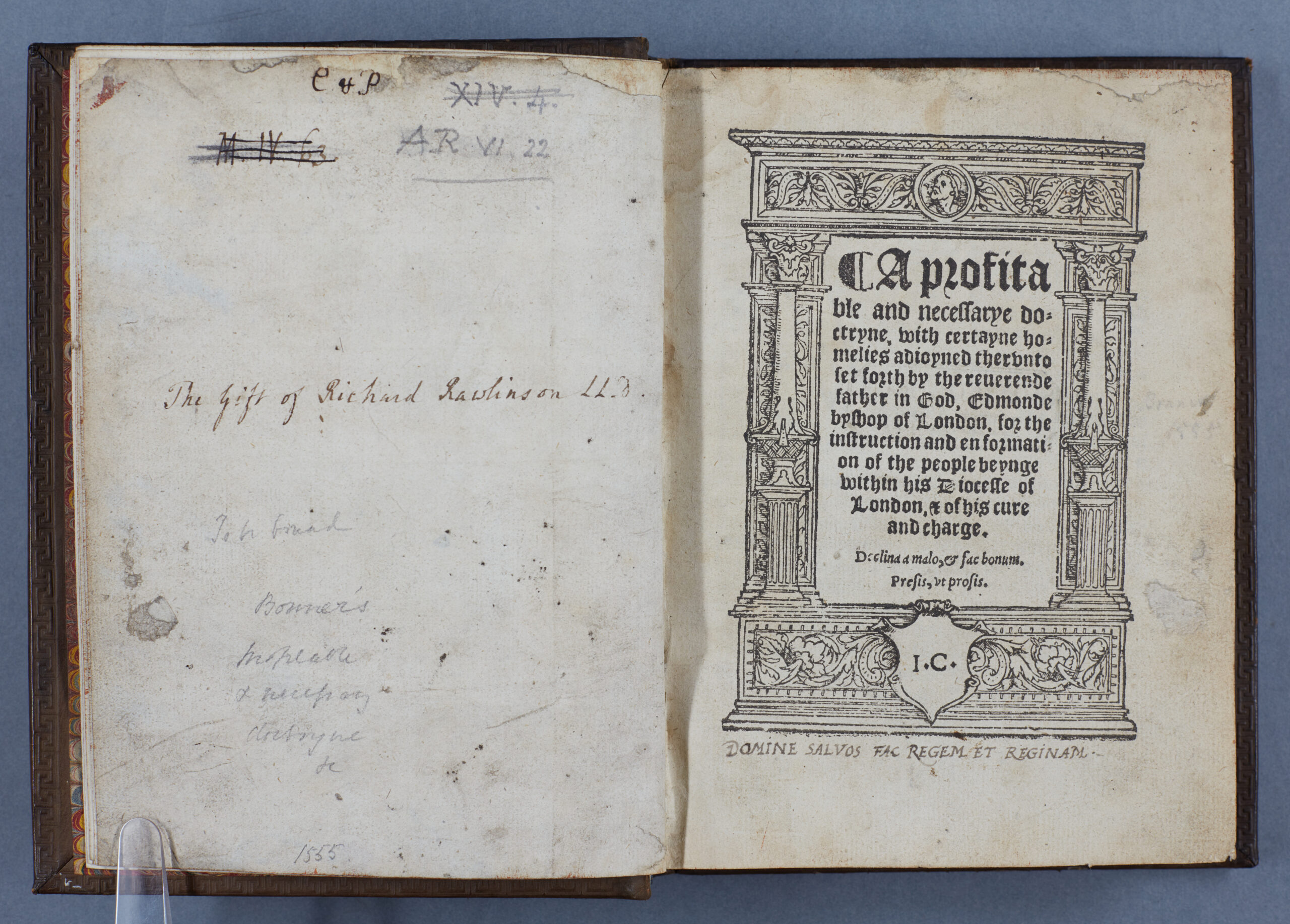

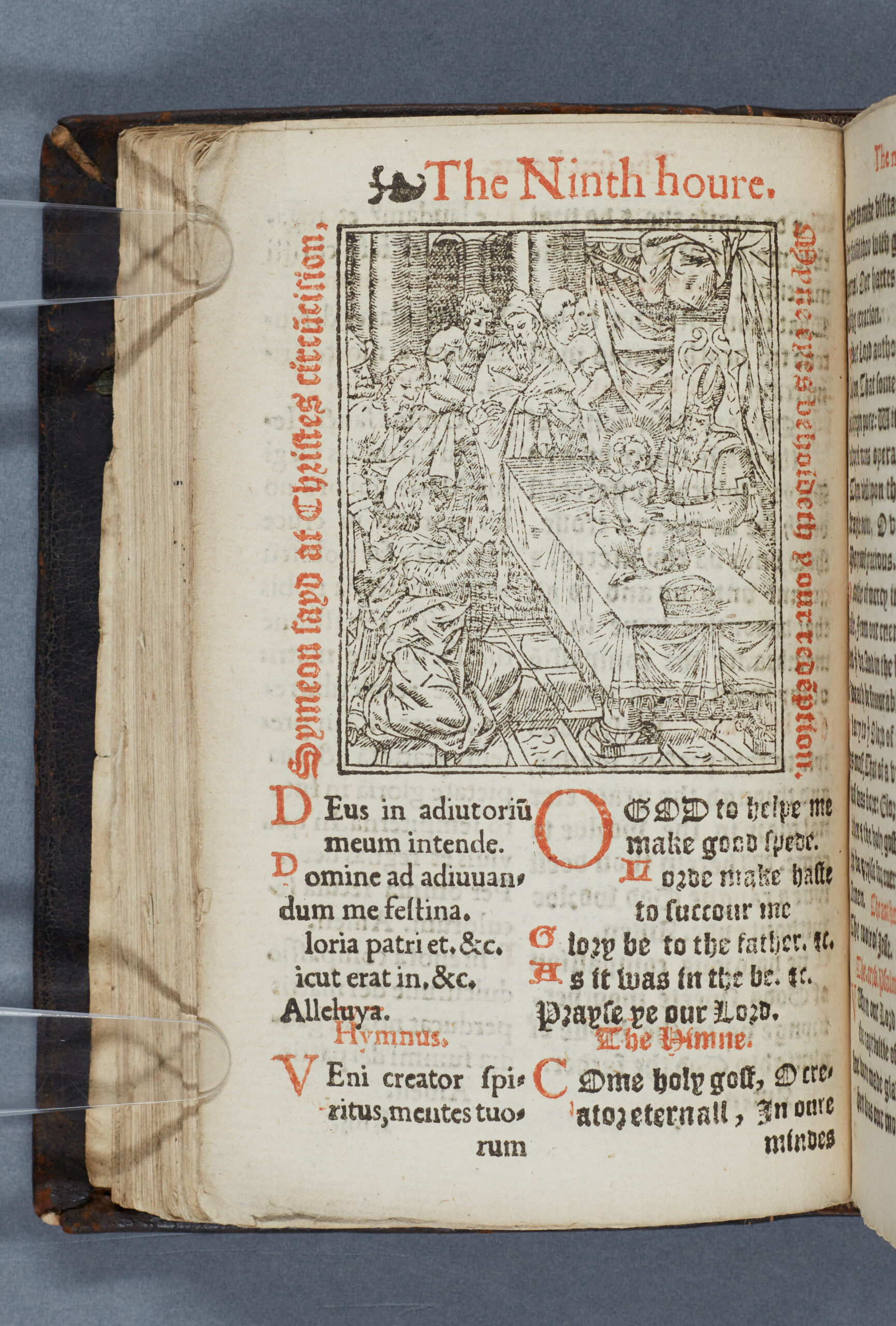

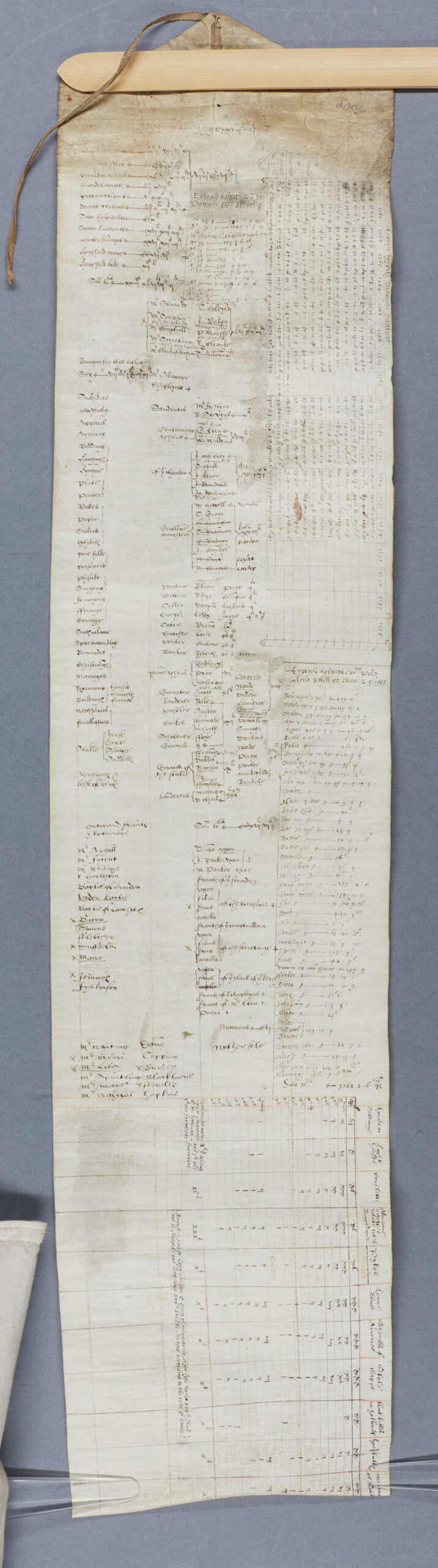

Restoring monasticism was central to Pole’s plans. In the pre-Reformation Church the religious houses had provided poor relief as well as providing preaching, hospitality, pastoral supervision, and intellectual leadership. In the short space of Mary I’s reign, several important monastic houses were refounded, including Westminster Abbey, Syon Abbey, and the Observant Franciscan house at Greenwich, where Pole was consecrated archbishop.

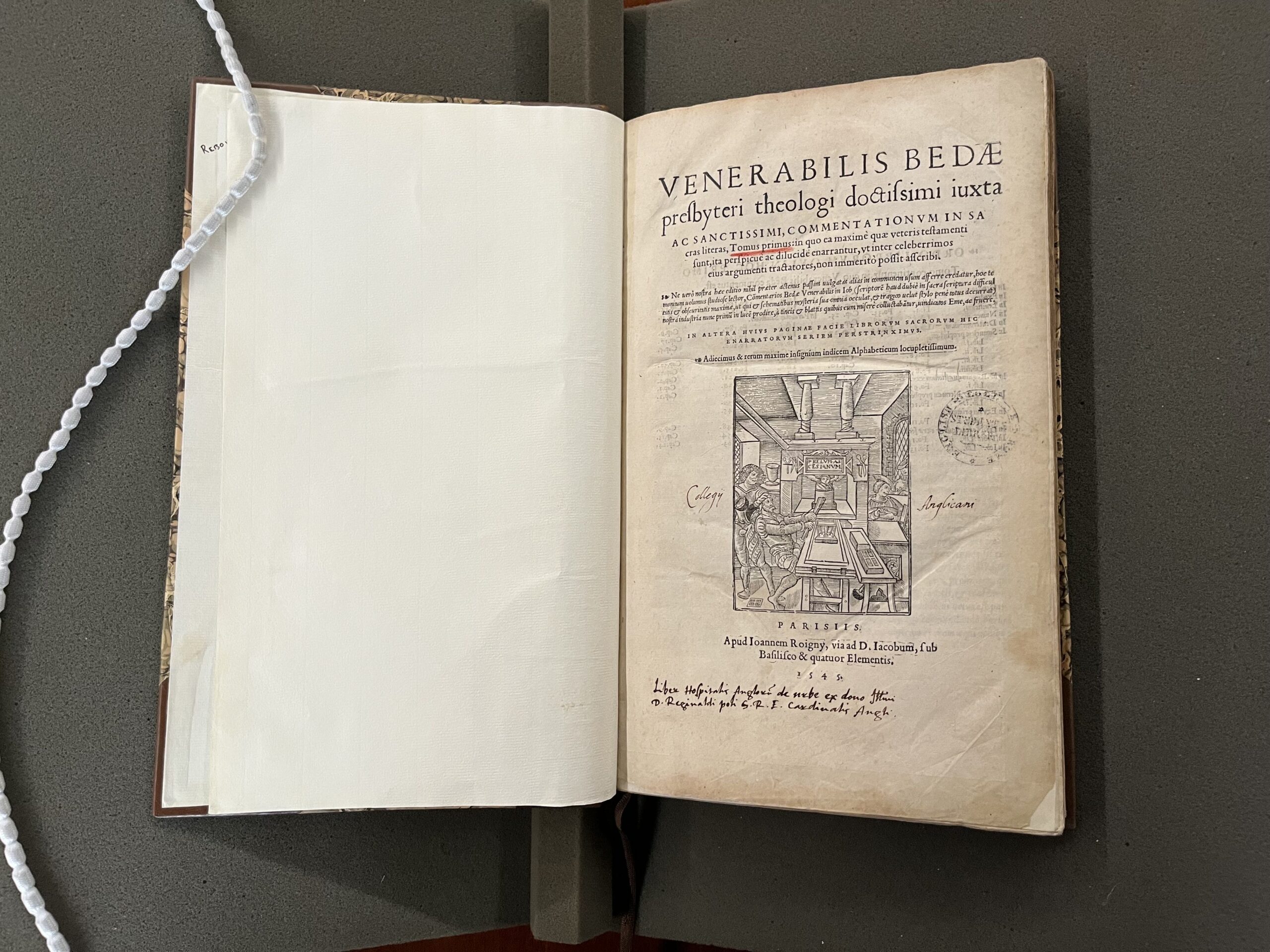

Saving souls required active, resident clergy guiding the faithful. Most decrees of Pole’s Legatine Synod were aimed at turning the clergy into prayerful, disciplined pastors who were the ‘fathers of the poor, the refuge and defence of the orphans, widows and oppressed’. They also insisted that clergy abstain from worldly concerns and be ‘assizzduously employed in the study of the Holy Scriptures’. Pole’s vision of the episcopate extended a vision of the godly household reminiscent of his own household back in Viterbo.

The heresy laws were revived in the parliament of January 1555, and between then and November 1558, nearly three hundred Protestants would be burnt at the stake. These persecutions have remained one of the most contentious elements in the history of Mary I’s reign, and were for many years the single defining feature of her rule. Pole’s complicity in this has been debated. It is true that he had argued at Trent that the only appropriate way to respond to heretics was with paternal love. But his involvement should be situated within a broader comprehension of his view of the Church, and his responsibilities as a leader of that Church

‘O Pole, O whirlpool, full of poison, that wouldst have drowned thy country in blood’

Richard Morison

‘The hope of England, glory of the Roman church, and light of Christendom’

Nicholas Sander

Queen Mary died on 17 November 1558, in Whitehall palace. Across the river at Lambeth, Pole too was close to death. Brought the news of Mary’s death, he wept, and spoke of his assurance that she was now in heaven. For once, however, there was no room for optimism as his mission of Catholic restoration began to crumble around him. Pole’s death, late that same day, might be said to have marked the death of the hopes of Catholic England.

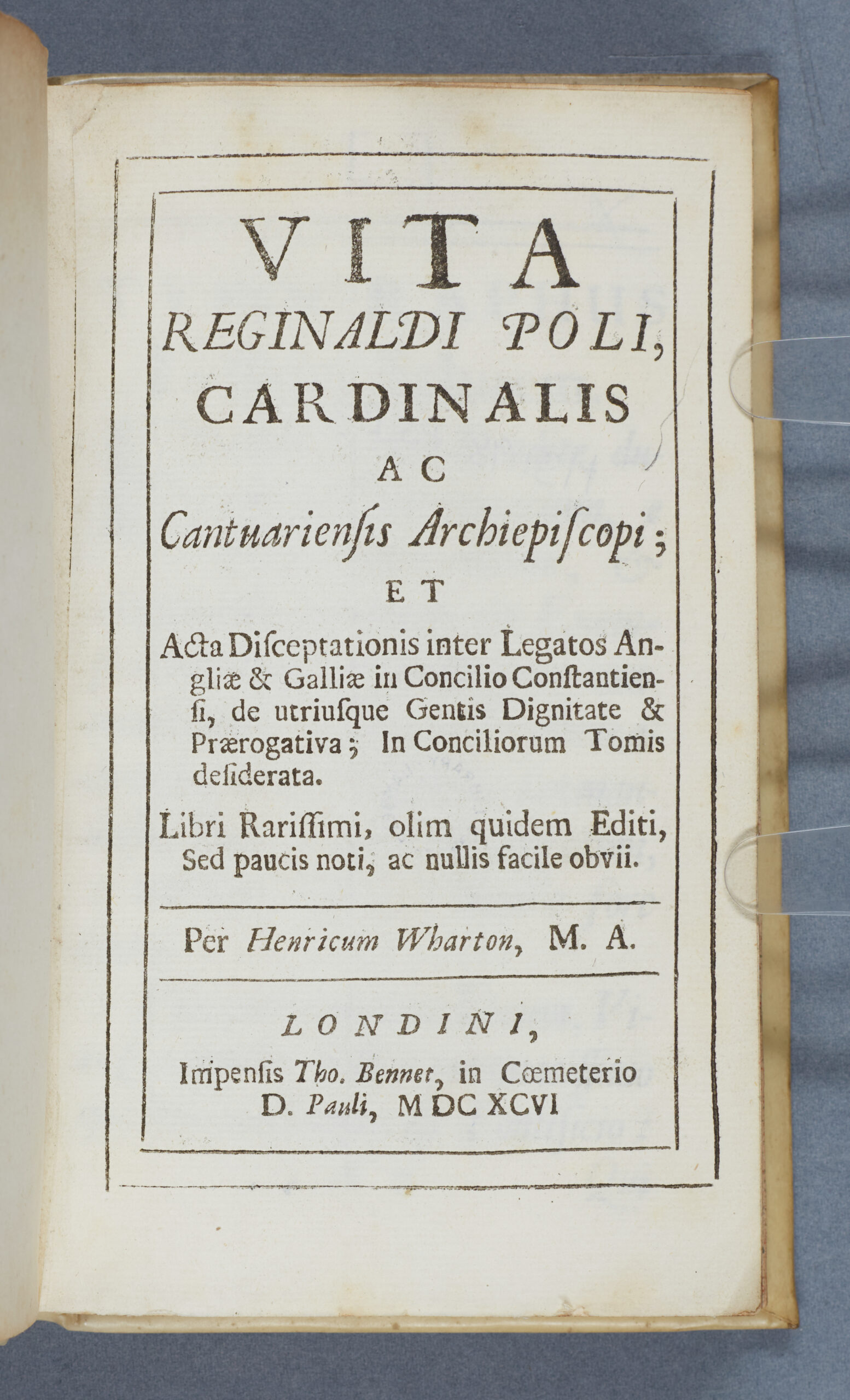

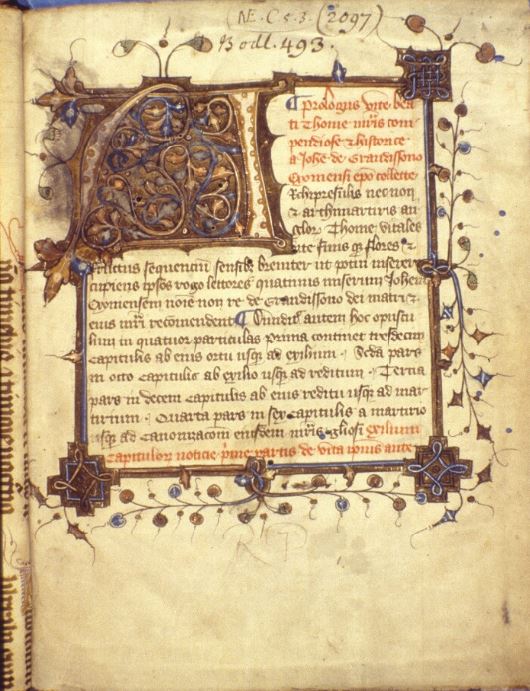

Since then, he has been at the heart of two contrasting legends of English history. In one he is seen as the cruel agent of ‘Bloody Mary’ and an instigator of the burning alive of approximately three hundred English and Welsh men and women for their non-Catholic religious beliefs. The other legend of Pole as a saint and almost a martyr for the Catholic faith began to form immediately after his death. Biographies of the late cardinal were written and edited by men who had known him, notably Ludovico Beccadelli, and by supporters, not least at New College in Oxford, where a third of the fellows refused to accept Elizabeth’s religious settlement of 1559, resigned their fellowships, and moved abroad.

The role that Pole had played, his legacy for English Catholics in particular and for the European Counter-Reformation more broadly, would remain as meaningful as it was complex.

![LPL [ZZ]1493.1f5v-6r The Nuremberg Chronicles](https://www.lambethpalacelibrary.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/1493.1f5v-scaled.jpg)

![LPL H1805.P6[**] Title Page](https://www.lambethpalacelibrary.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/H1805_TP.jpg)

![LPL [ZZ]1536.1](https://www.lambethpalacelibrary.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/1536.1_-scaled.jpg)

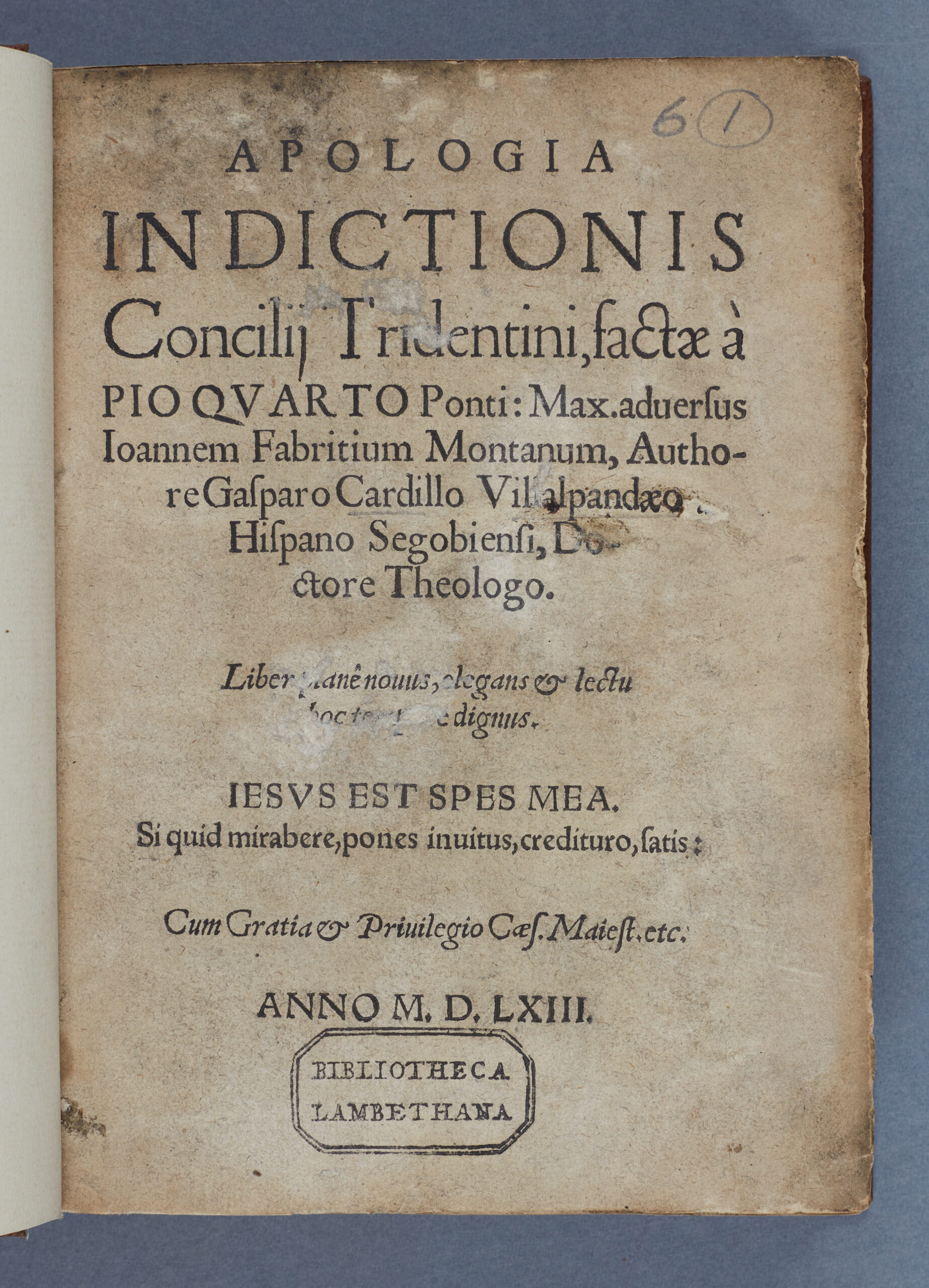

![LPL [ZZ]1562.2.10_TP](https://www.lambethpalacelibrary.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ZZ1562.2.10_TP-scaled.jpg)

![LPL H5067.P6 [**]](https://www.lambethpalacelibrary.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/H5067xx.jpg)

![LPL H1780.S2 [*]](https://www.lambethpalacelibrary.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/GH-H1780.S2_TP.jpg)

![LPL [ZZ]1550.06.07_TP](https://www.lambethpalacelibrary.info/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ZZ1550.06.07_TP-scaled.jpg)