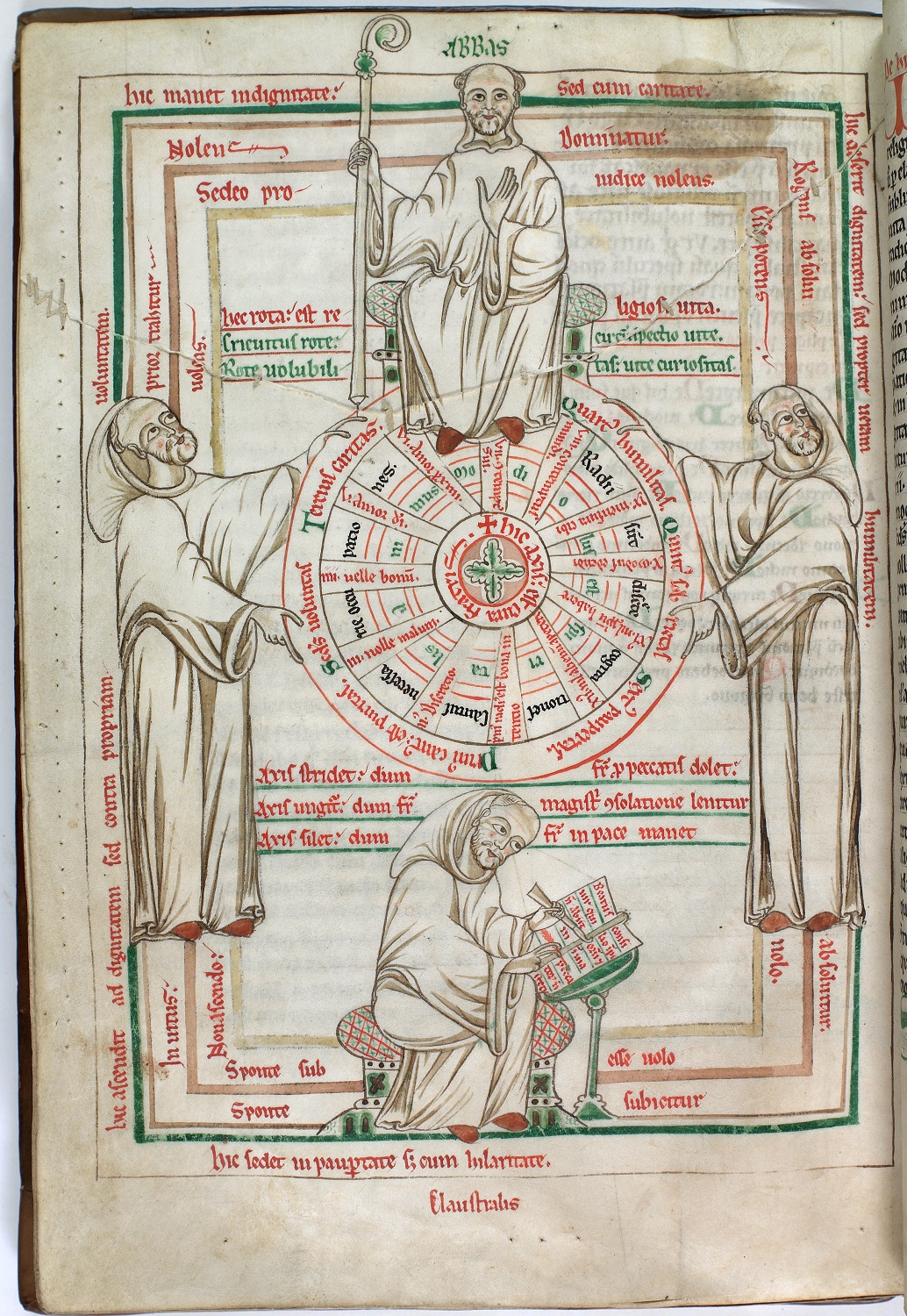

The Wheel of True and False Religion

This didactic text, written by Hugh de Fouilloy, a twelfth-century Augustinian monk, was widely read by contemporaries. The illustration provides a visual guide to leading a virtuous religious life and imitates the familiar concept of the wheel of fortune. At the bottom of the page, an industrious monk, depicted as a scribe, writes the opening of the first psalm. The monk ascends unwillingly through the position of prior on the left and ultimately to that of abbot, at the top of the page. He governs honourably, but relinquishes the position of abbot out of humility. The diagram is mirrored by the wheel of false religion on f.89r.

By the end of the twelfth century the volume was at the Cistercian abbey of Buildwas, Shropshire, and entered Lambeth’s collections in the early seventeenth century. A repair, possibly contemporary with the volume’s original use, is visible across the top third of the page.

MS 107, f. 84v

England, second half of the twelfth century

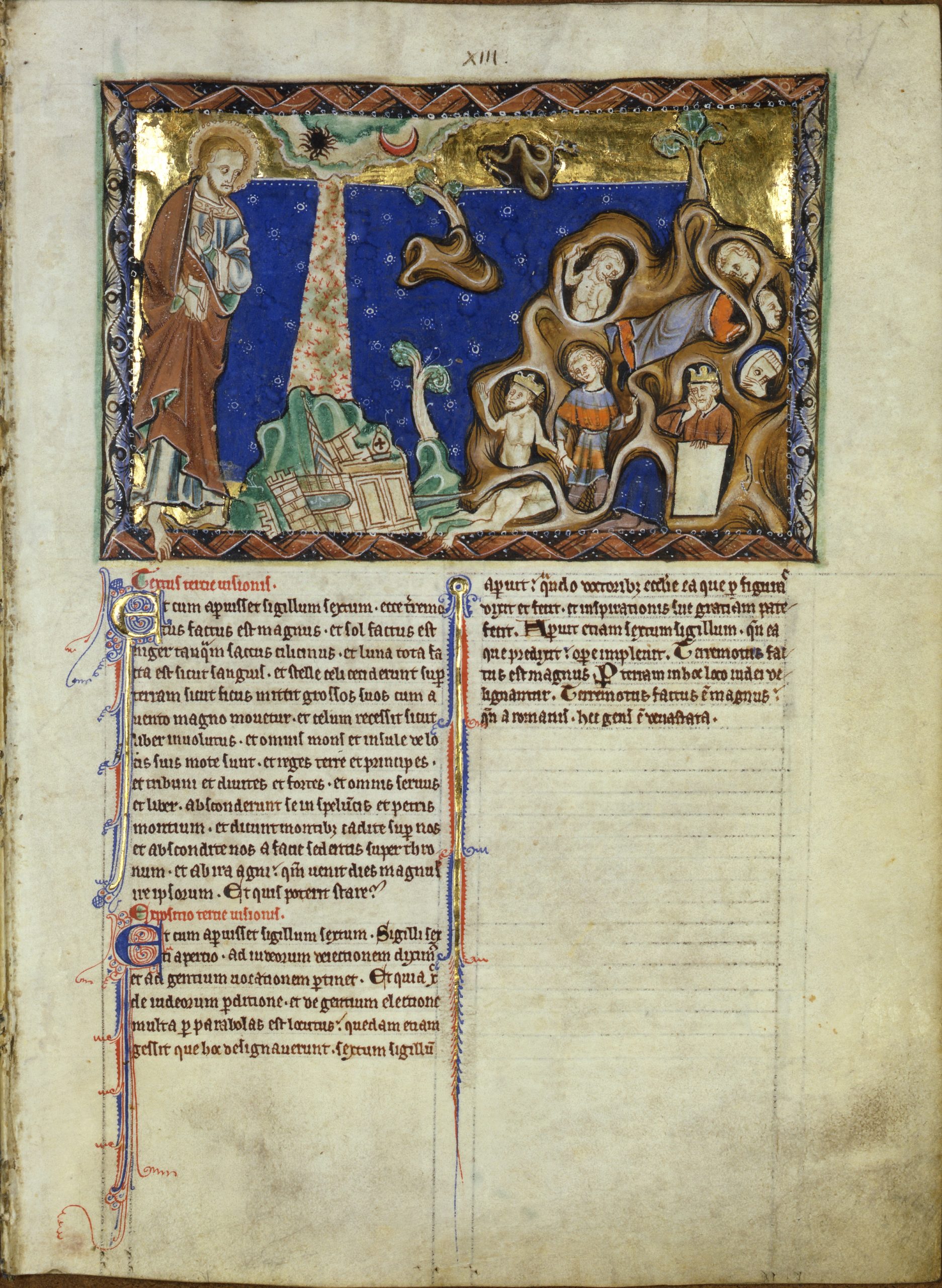

The Lambeth Apocalypse

This spectacular manuscript is a richly illustrated text of the Book of Revelation, accompanied by a theological commentary. Created in the thirteenth century, the work describes the events leading up to the Last Judgment and the triumph of the righteous over evil. The manuscript was produced for Lady Eleanor de Quincey (d. 1274), Countess of Winchester. It is a striking visual example of the piety of many medieval aristocratic women, and of the role they played in the patronage of scribes and illuminators.

We see here an earthquake shaking the ground, while the sun turns black and the moon the colour of blood; all ranks of people hide themselves in caves to avoid the wrath of God (Revelation 6:12-15).

MS 209, ff. 7r

London?, c.1260-1267

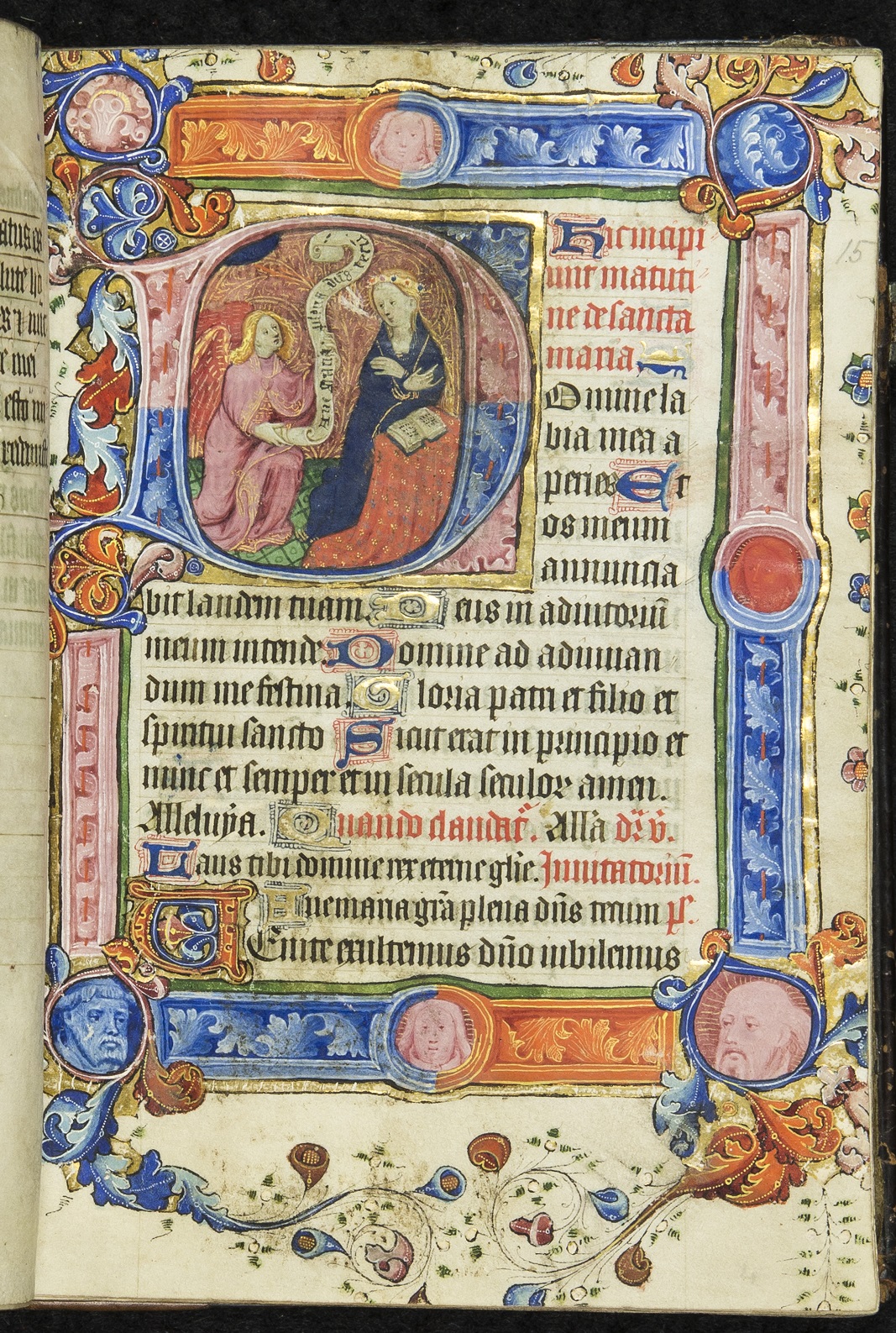

The Hours of Richard III

Books of hours (Horae) were books of private devotions for use by the laity. This example was once owned by Richard III. Several devotions were added for Richard by a professional scribe, the most important of which is the so-called ‘prayer of Richard III’. Written in the first person, it is a prayer for, amongst other things, protection against his enemies and for reconciliation with them. It was not composed for him but is a variant of a standard prayer which circulated widely in the fourteenth century and was used by Emperor Maximilian I and Richard’s contemporary Alexander, Prince of Poland, amongst others.

The illustration showing the Annunciation accompanies the text of matins in the Hours of the Virgin.

MS 474, ff. 14v-15r

London, c.1420

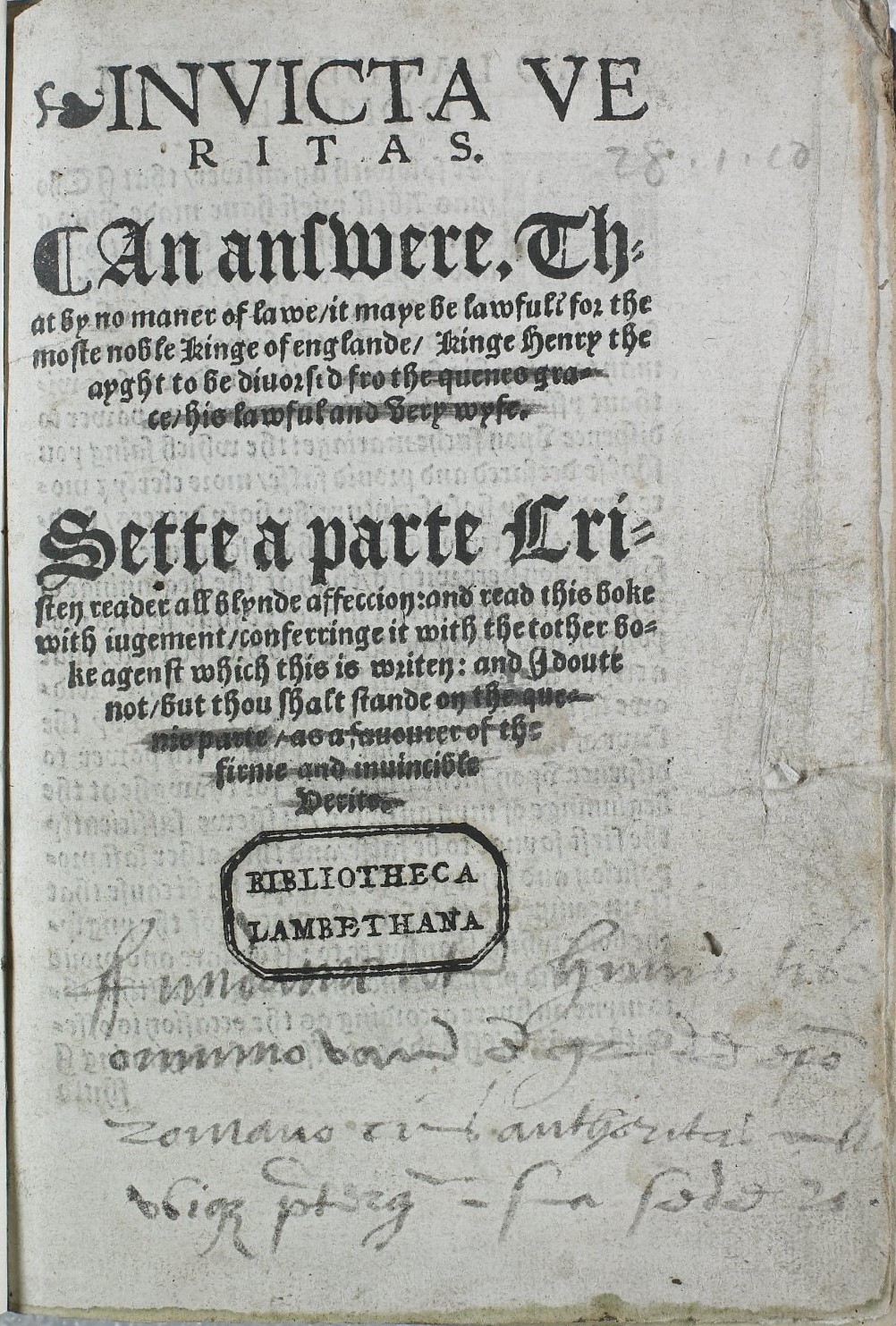

Henry VIII’s marginalia

The origins of the Reformation in England lay with Henry VIII’s negotiations for a divorce from his first wife Catherine of Aragon. The marriage had failed to produce a male heir and Henry had become infatuated with one of his wife’s ladies-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn. While Henry sought an annulment from the Pope, the Queen’s chaplain, Thomas Abell, published this defence of the validity of the marriage. The furious King had Abell thrown into prison and eventually executed for treason on 30 July 1540. This particular copy of Abell’s book comes from Henry’s own library and contains annotations by the King himself showing his angry disagreement with the text. On the title-page Henry has written ‘Fundament[um] huius libri omnino vanum’ (‘The grounds of this book are wholly worthless’) and he has added further scathing comments in the margins.

Thomas Abell, Inuicta veritas [Antwerp, 1532]

[ZZ]1532.4.01

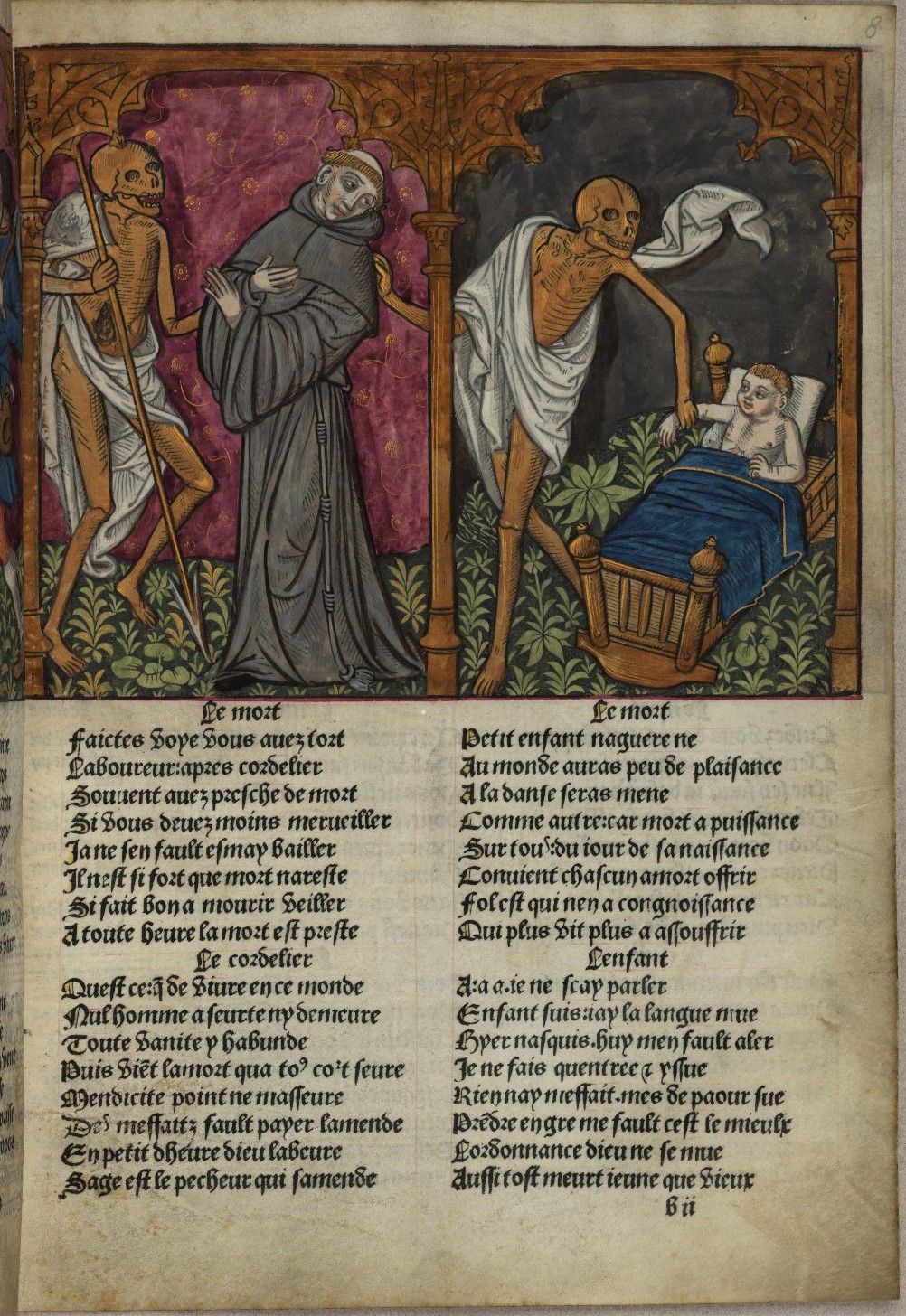

The Dance of Death

The Danse macabre (‘Dance of death’) was a popular medieval allegory reminding people of the universality of death and encouraging them to reflect on the condition of their souls. This theme is first known from a mural painting made in Paris in 1424, depicting grinning corpses leading people from all walks of life in a dance to the grave. The figures shown often included an emperor, merchant, priest, labourer and child, suggesting that no matter one’s wealth or station in life, death unites us all. By the end of the 15th century, the Danse was appearing in printed form. This example, published in 1492 by Antoine Vérard, includes 35 hand-coloured woodcuts accompanied by verses in French. Only one other copy is known to survive.

Danse macabre (Paris: , 1492)

MS 279

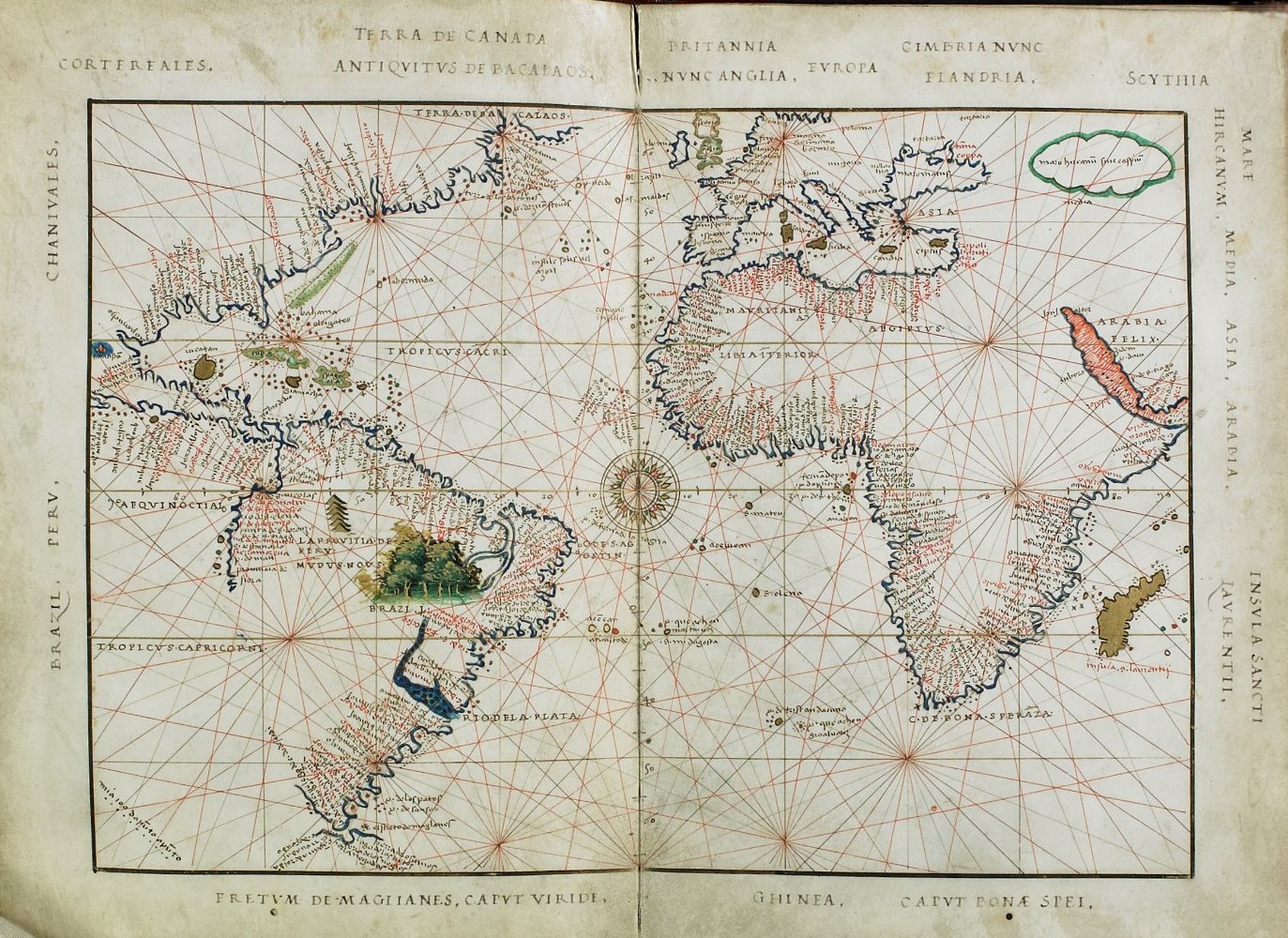

Portolan Atlas

The portolan chart was a navigational aid which originated in the Mediterranean in the 13th century. This atlas of 12 such charts is thought to have been made by the Genoese chart-maker Battista Agnese in Venice in about 1543, probably as a diplomatic gift for presentation to King Henry VIII. The small format and the marginal notes later inserted in this atlas, which is illuminated with the English royal arms, have led to suggestions that it may have been used to teach the young Edward VI while Prince of Wales.

The opening on display shows the continents of Africa and Europe and the western coast of the Americas, with the equator, tropics and Brazilian rainforest marked.

MS 463, ff. 4v – 5r

Venice, c.1543

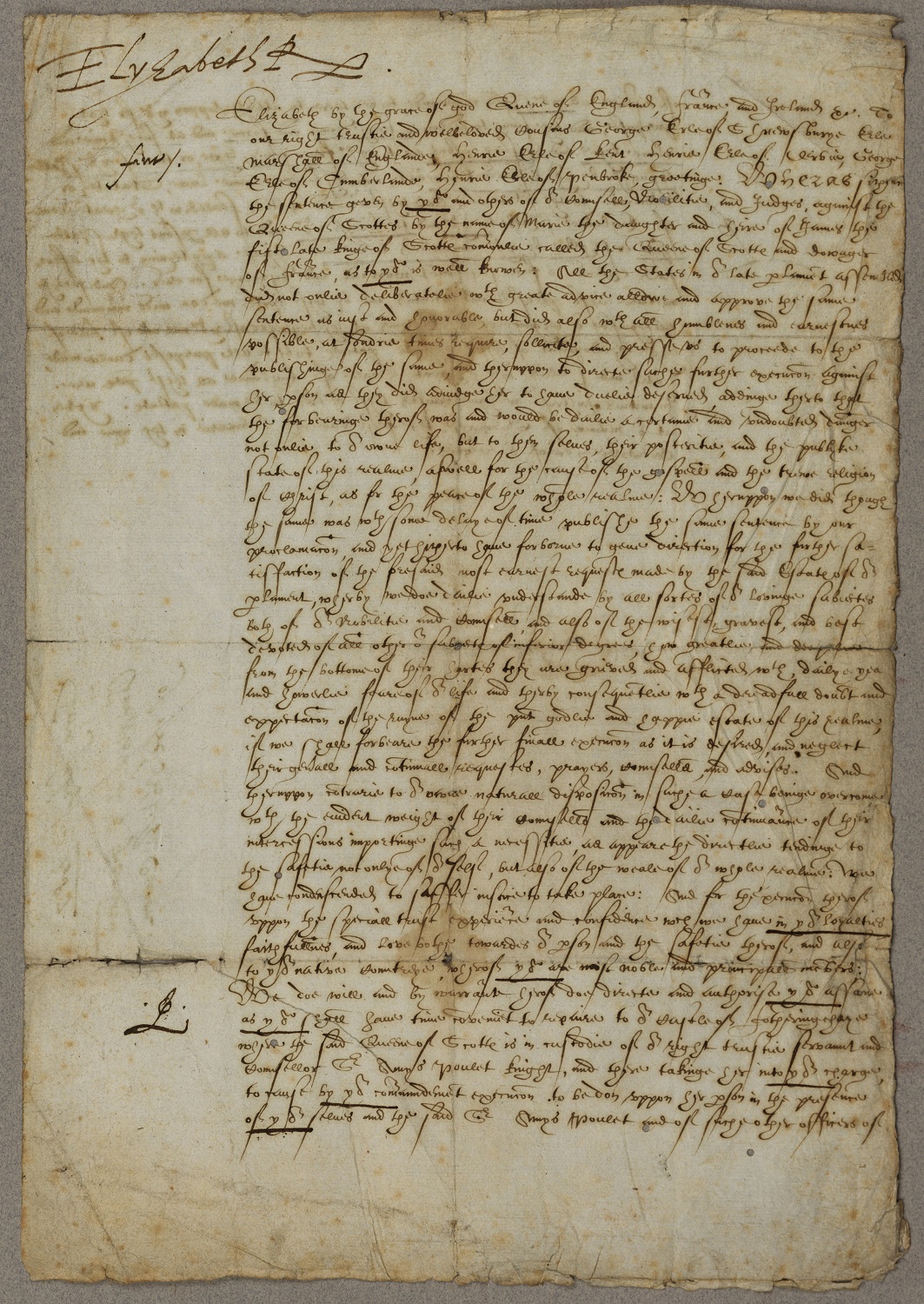

Warrant for the execution of Mary Queen of Scots

Although the official religion of England in the late sixteenth century was Protestant, much of the country remained privately Catholic, and Elizabeth I’s reign was troubled by religious tension. Jesuit missionary priests were hunted down and executed, and domestic celebration of the Latin mass by ‘recusants’ was rooted out. The most notorious incident was the execution in February 1587 of Mary, Queen of Scots, for involvement in the Babington Plot against her cousin, Elizabeth.

This is a contemporary copy of the warrant for Mary’s execution, with annotations by Robert Beale, Clerk of Privy Council. Elizabeth had hoped to avoid sanctioning the death of her cousin, preferring a private assassination. The original warrant was destroyed, possibly by Elizabeth: the document authorised regicide for the first time, and later created a precedent for the execution of Mary’s grandson Charles I in 1649.

MS 4769, f. 1r

Greenwich, 1 February 1587

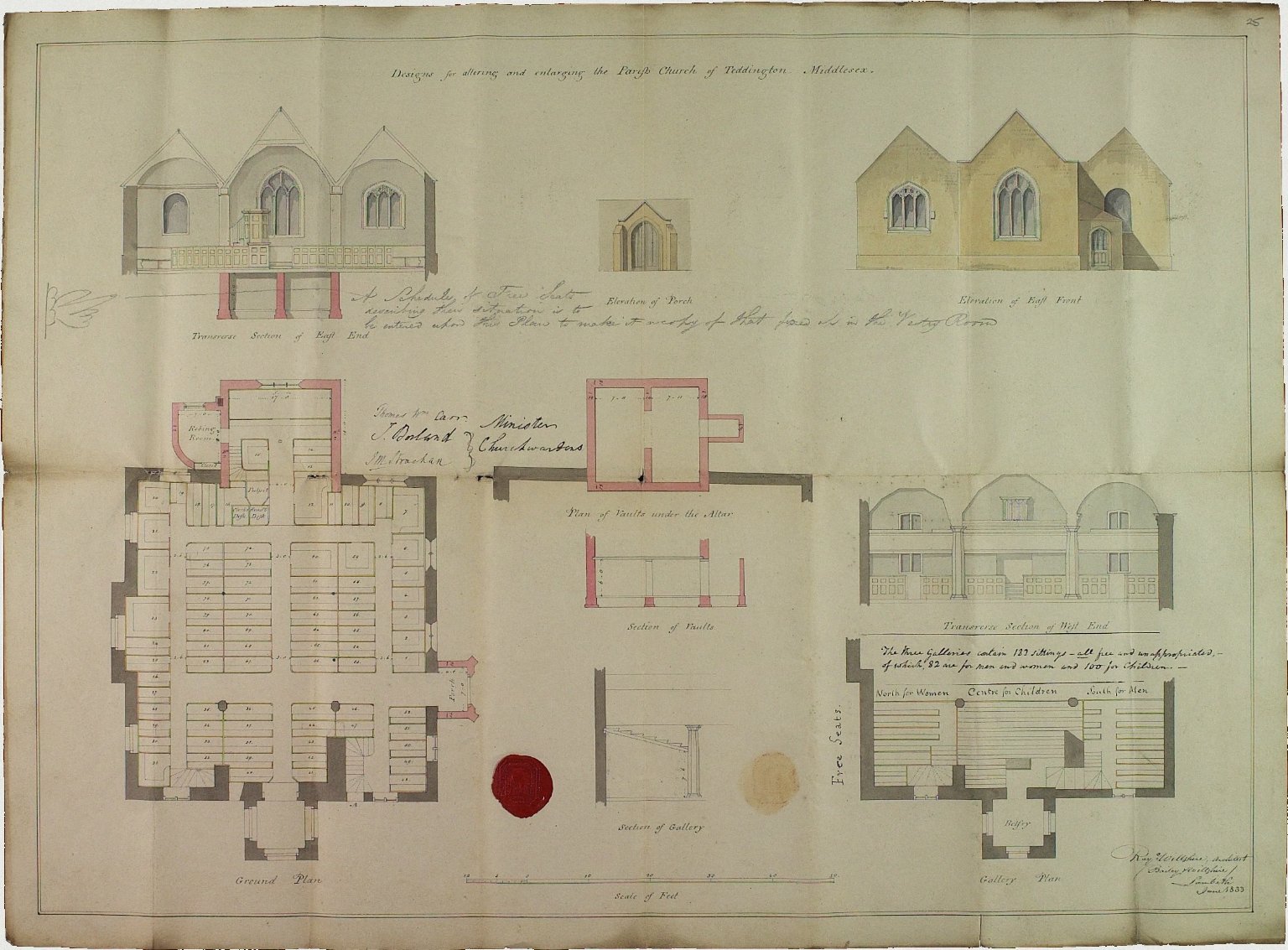

Plan of Teddington Church

The records of the Incorporated Church Building Society (ICBS) comprise the minute books and some 16,000 files relating to applications for grants for the building and restoration of churches throughout England and Wales, from the foundation of the Society in 1818 until 1982. Applications were made on a standard form which included data on the population and character of the parish, as well as information on the church building. The files are accompanied by over 13,000 plans showing cross-sections and elevations of the churches.

This plan was created and signed in 1833 by the architect Raymond Willshire and shows proposed alterations and enlargements of St Mary’s Church in Teddington, Middlesex. The signatures of the churchwardens can also be seen.

ICBS 1574

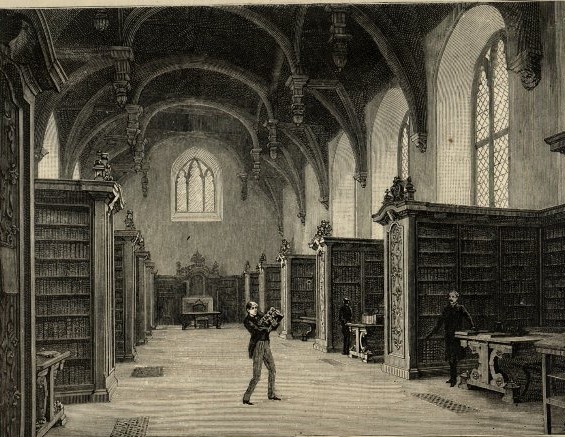

The Library in the Great Hall of Lambeth Palace, 1886

The first hall on the site of the Great Hall was probably built around 1200, but it was ruined during the English Civil War, when troops loyal to Oliver Cromwell occupied Lambeth Palace. The current Great Hall, depicted here, was built under the direction of Archbishop William Juxon between 1660 and 1664, in a medieval style.

As part of the major renovations by the architect Edward Blore in 1829, commissioned by Archbishop William Howley, Lambeth Palace Library was transferred from the nearby cloister to the Great Hall, which served as the Library’s reading room. A muniment room for the manuscripts and records was constructed over an adjoining archway.

The Graphic, 31 July 1886, p. 113

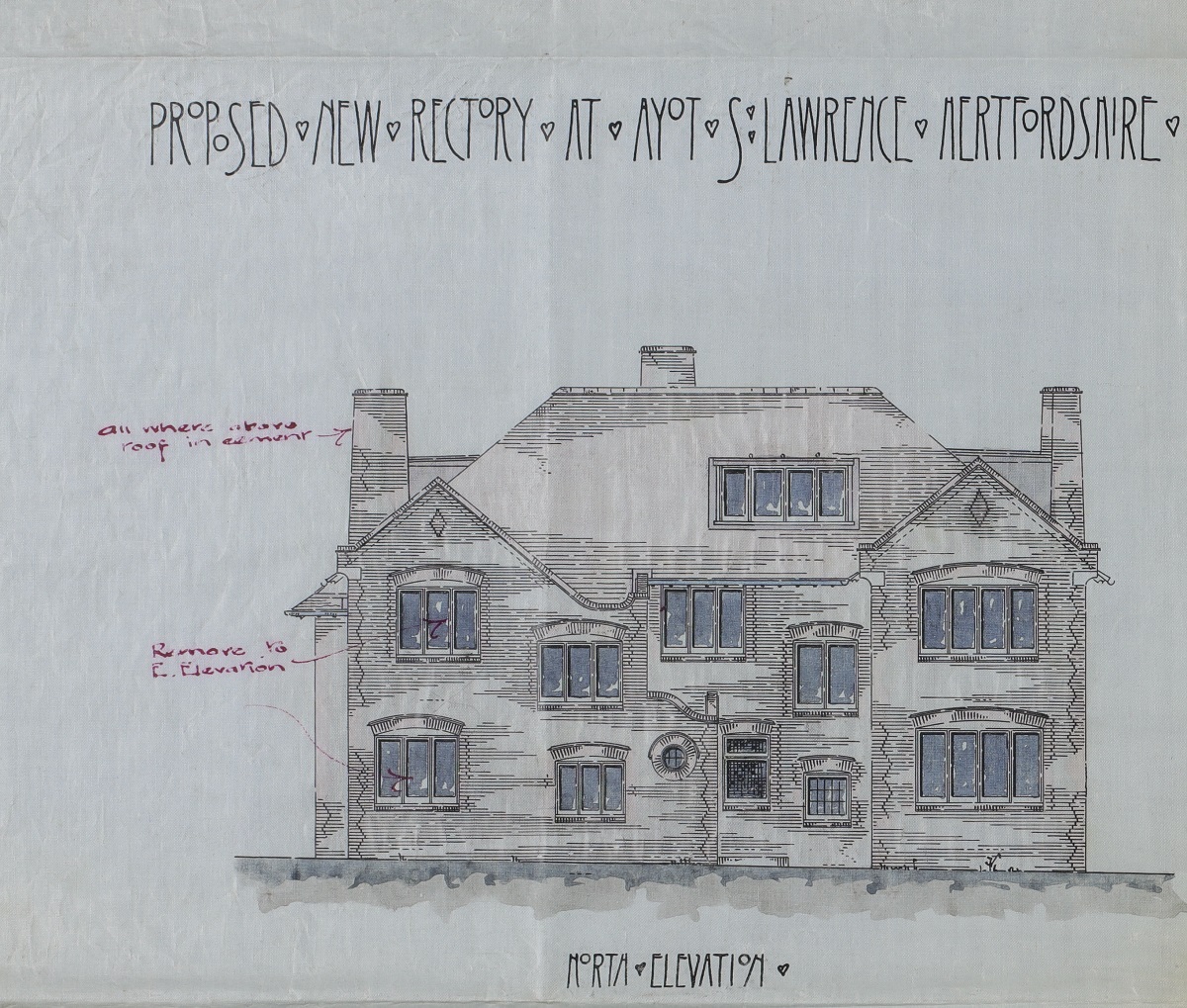

Ayot St Lawrence Parsonage House

The house was built as the New Rectory for Ayot St Lawrence in 1902. It was designed by architects Smee and Mence in the Arts and Crafts style, with stained glass windows and hearts cut into the banisters. The house was not used as a rectory for long as it was soon rented out to the dramatist George Bernard Shaw and his wife. The Shaws bought the house in 1920 for £6,332 and it became their most permanent home, renamed ‘Shaw’s Corner’. It became a National Trust property in 1951, after George Bernard Shaw’s death.

This plan is one of a large series of parsonage plans created within the architects department of the Queen Anne’s Bounty (QAB), documenting the improvement of existing parsonage houses and the construction of new ones financed by the QAB.

QAB/7/6/E3239

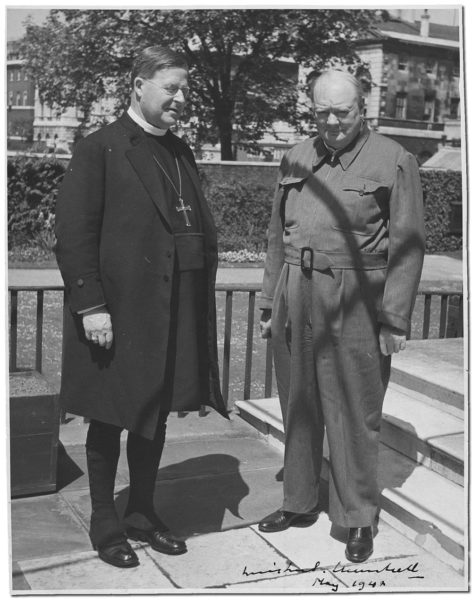

Archbishop William Temple and Winston Churchill, May 1942

Despite being Archbishop of Canterbury for less than three years, William Temple was one of the most influential figures to hold the office in the 20th century. A prolific writer, his work Christianity and Social Order played an important role in the creation of the welfare state.

Having served as Bishop of Manchester and Archbishop of York, Temple was enthroned as Archbishop of Canterbury in April 1942, following the retirement of Cosmo Gordon Lang. His record of achievement was such that he was the obvious choice. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, with whom Temple is pictured here, is believed to have described him as ‘the only half a crown article in the sixpenny bazaar’.

As Archbishop of Canterbury, Temple inaugurated the British Council of Churches and was largely responsible for ensuring church support for R. A. Butler’s Education Act of 1944, about which he spoke frequently in the House of Lords. But his health deteriorated sharply, probably exacerbated by overwork. He was taken ill in early October 1944 and died later that month.

MS 4515, f. 85

The First Lambeth Conference

The four-day meeting in September 1867 of bishops from across the Anglican Communion, known at the time as the ‘Pan-Anglican Synod’, is recognised as the first Lambeth Conference: the assembly of bishops, convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury, which has taken place roughly every ten years since.

Archbishop Charles Longley, seen here in the centre directly above the bishop seated on the steps of Lambeth Palace, had invited 148 bishops from across the world for a process of ‘brotherly consultation’ and 76 attended. The meeting was dominated by debate concerning the Bishop of Natal, John Colenso and the attempt by Bishop Robert Gray of Cape Town, who is seated on the steps, to elect a replacement in view of what he saw as Colenso’s heretical practices.

The gathering was widely seen as a failure, as many bishops had declined to attend, and there was no resolution of the Colenso question. However a meeting of bishops of the Anglican Communion had been established in principle, and the second conference took place in 1878.

MS 1728, f. 27

Treasures II ran from 10 January 2022 until Friday 8 April 2022.